Unswimmable, unfishable rivers, lakes, and Sound—and what’s necessary to restore them to health.

Contents

CT Stormwater Pollution

Municipalities Can Help

MS4 Regulatory Requirements

Mapping & Tools

Funding Options

Municipal Success Stories

Additional Resources

Contact

What is MS4?

Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) refers to a collection of structures designed to gather stormwater and discharge it into local streams and rivers. An MS4 is a conveyance or system of conveyances that is:

- owned by a state, city, town, village, or other public entity that discharges to waters of the U.S.,

- designed or used to collect or convey stormwater (e.g., storm drains, pipes, ditches),

- not a combined sewer, and

- not part of a sewage treatment plant, or publicly owned treatment works.

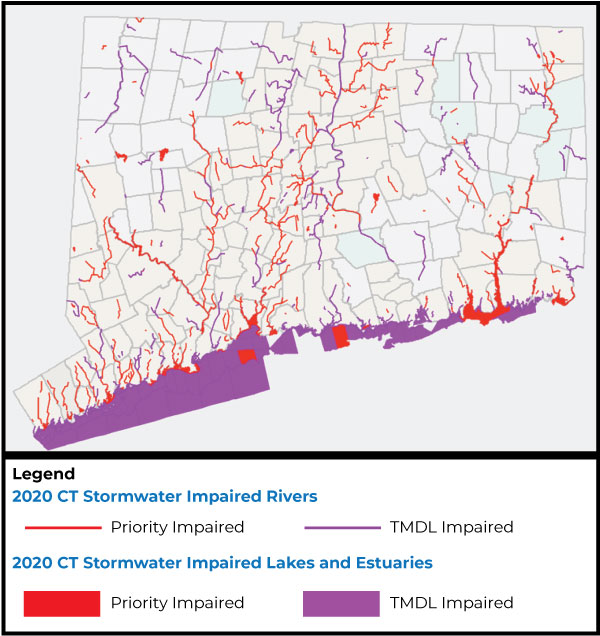

Connecticut waterbodies impaired by pollution

Connecticut waterbodies impaired by pollution

In spring 2021, Save the Sound investigated Connecticut municipalities’ compliance with Clean Water Act requirements for municipal stormwater. To protect the health of local waters, the clean water act requires towns with Municipal Separate Storm Sewer Systems (MS4) to take certain measures to protect water quality. Alarmingly, our research showed that municipalities across the state are discharging stormwater pollution that is making local streams, lakes, and estuaries unsafe for swimming and aquatic life and violating federal water quality standards. Very few municipalities are in full compliance with their obligations to protect local water quality.

This website gathers information about the impact of municipal stormwater pollution, what the Clean Water Act requires of municipalities, and resources for municipalities that are working to meet their federal Clean Water Act obligations: funding sources, mapping, examples of successful action, and more.

The Problem of Connecticut Stormwater Pollution

Stormwater runoff is one of Connecticut’s most serious sources of local water pollution. It occurs when rain lands on impervious surfaces such as sidewalks, roads, roofs, and parking lots picking up pollutants such as oil, antifreeze, heavy metals, pesticides, and bacteria and transporting the pollutants to lakes, streams, and rivers like the Connecticut and the Quinnipiac. In a natural environment, rainwater soaks into the soil, where it’s filtered and can replenish groundwater. On impervious surfaces, however, rainwater and pollution are directly channeled to rivers, lakes, and estuaries. According to the Housatonic Valley Association, 70 percent of Connecticut’s fresh water bodies are unfit for swimming at least part of the year, compared to 55 percent nationwide. This is largely due to stormwater pollution. The pollutants also end up in Long Island Sound, where they harm marine life and close beaches and shellfish beds.

Cartoon by George Wills in “Beaches and Bacteria,” Virginia Water Central, 2004/2014.

Moreover, extreme precipitation events are becoming more common, a concern on full display in 2021, as multiple tropical storms brought serious flooding and water pollution to our region. If the threat of stormwater is not properly addressed, increasing downpours and flooding will likely exacerbate water quality issues and overwhelm inadequate stormwater management systems, resulting in increased environmental and financial stress in our region.

Municipalities Can Reduce Stormwater Pollution

To stop this pollution, the federal Clean Water Act requires certain entities, such as municipalities, to register for a stormwater permit and comply with its terms.

In Connecticut, a cornerstone of our municipal stormwater permits is the disconnection of impervious surfaces. This was a result of a negotiated agreement in 2016 and 2017 among municipalities, DEEP, and Save the Sound regarding the most effective and cost efficient ways to address stormwater pollution. Starting in the summer of 2020, municipalities are required to disconnect one percent of impervious surfaces per year to reduce their polluted stormwater discharges. Most commonly, “disconnection” means retrofitting surfaces to allow water to infiltrate into groundwater by creating green infrastructure (rain gardens, bioswales, etc.) to absorb and filter the water. Municipalities must provide retrofit plans to show how they will reduce polluted runoff.

There are measures that municipalities must also take to reduce stormwater pollution to local waterbodies. Towns were required to have mapped their stormwater systems and outfall locations—the places where stormwater actually enters a waterbody. Without knowing their stormwater system there is little they can do to control it. Because land use in Connecticut is regulated at the local level, municipalities were also required to pass ordinances requiring land developers to reduce stormwater impacts from their sites. Finally, stormwater reports are to be produced annually and made accessible to the public. It’s in these reports that the public, DEEP, and EPA can track a municipality’s compliance with the MS4 permit, including impervious surface disconnection. This information is supposed to be filed with DEEP and accessible through town websites.

When the 2017 permit was issued, the state realized that towns would need support in understanding and fulfilling their obligations. Accordingly, there have been extensive resources and educational outreach efforts directed at municipalities. The state has contracted with UConn’s Center for Land Use Education and Research (CLEAR) and its Nonpoint Education for Municipal Officials (NEMO) program to provide support and resources to towns. This has included notice of upcoming requirements, trainings on how to implement certain measures, and even comprehensive mapping of each municipalities’ impervious areas.

Thus, there is no reason that a town should not be aware of and able to meet its federal Clean Water Act obligations regarding stormwater pollution.

Clean Water Act Stormwater Requirements for Connecticut

To address the impacts of stormwater pollution, all municipalities must comply with a “general permit,” issued most recently in 2017 to all municipalities that meet certain requirements for population density. The following links provide background on the required pollution control measures:

CT Mapping & Tools to Help

Mapping stormwater systems and impervious surface is a requirement in the new MS4 permit, and there are a host of resources available to help guide municipalities through this process. NEMO has created an extensive guide, along with webinars, workshops, and presentations.

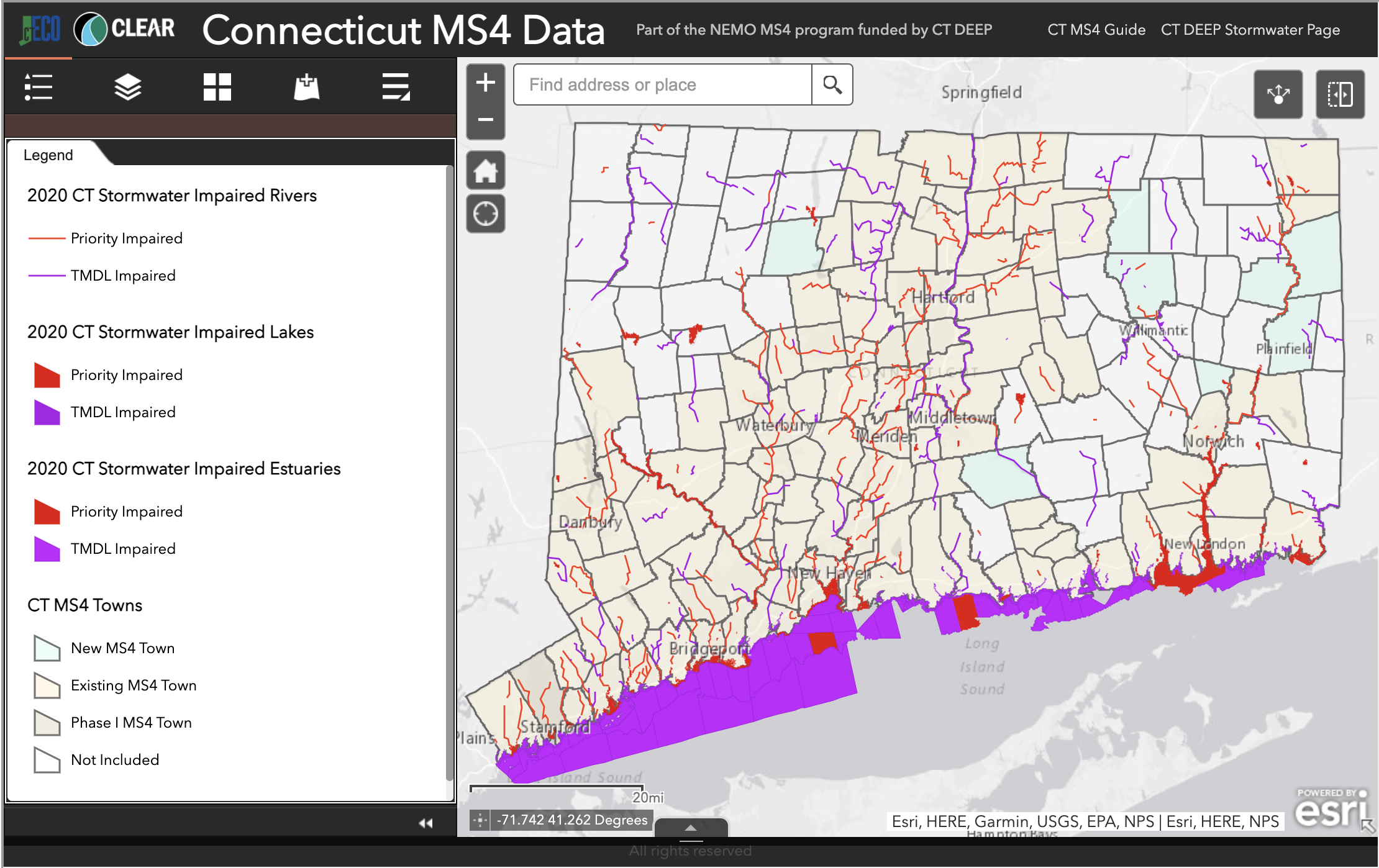

NEMO has compiled an interactive map with existing and new data to help municipalities meet several MS4 permit requirements.The map below shows MS4 communities and stormwater polluted waterbodies within these communities in red. As the map shows, there are stormwater-polluted streams, lakes, and estuaries in virtually every community in Connecticut.

Additional tools and maps:

- In response to the new MS4 permits, the Naugatuck Valley Council of Government’s has provided extensive guidance and tools for the municipalities within its regional planning district.

- The FEMA Resilience Analysis and Planning Tool (RAPT) allows stakeholders the ability to analyze the interplay of multiple risk factors to determine the need for future planning.

Funding Options

Funding clean water and habitat resiliency can be expensive, but it’s well worth it. Clean water is an irreplaceable natural resource and ability to swim and fish in local rivers, lakes and estuaries adds immensely to local economies. There are also co-benefits in terms of flood relief. Thankfully, municipalities have an abundance of opportunities at the state and federal level to access funding, as well as private foundations and innovative local fee structures. A detailed list is provided below:

Income from Stormwater Authorities

A stormwater authority is a public entity that collects fees for managing stormwater runoff. Stormwater authorities can help Connecticut municipalities bridge the funding gap and make these solutions attainable and sustainable. Under state legislation passed in 2021, any municipality may now establish a stormwater authority. Tying fees to activities related to flood or stormwater management also provides an opportunity to offer incentives to promote individual actions at the homeowner scale that can help the broader stormwater management system deal with water pollution and flooding events. New London has successfully operated a stormwater authority, with reasonable rates, for several years. Learn more about how your community can benefit from a stormwater authority from NEMO.

The EPA has put together guides on using stormwater fees as well as employing incentive programs.

Federal

- The Water Finance Center provides financing information to help local decision makers make informed decisions for drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater infrastructure to protect human health and the environment.

- FEMA’s hazard mitigation program, pre-disaster program, and others help mitigate long-term disaster damage, reconstruction, and repeated damage.

- The National Coastal Resilience Fund is a partnership between NOAA, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and other government and private sector partners with the goal of restored coastal ecosystems.

- EPA’s Smart Growth Grants occasionally offer grants to support activities that improve the quality of development and protect human health and the environment.

- Environmental Justice Initiative focuses on organizations that look to solve environmental and public health issues at the local level.

- EPA’s Brownfields Jobs Training Grants Program is refocusing the competition on training activities that support assessment, cleanup, and preparation of brownfield sites for reuse.

- NOAA’s Climate Program Office is offering multiple funding opportunities for climate adaptation.

- The EJ4 Climate Grant Program supports underserved, vulnerable, and indigenous communities to mitigate climate impacts.

- NRCS – EQIP, Conservation Innovation Grants are receiving applications for programs that give priority to conservation practices and systems that will result in greater environmental benefits for national, state, and/or local natural resources.

- ARPA Funds – The treasury is accepting requests from eligible state, local, territorial, and Tribal governments that are requesting Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds.

Connecticut State

- The Clean Water Fund has requirements for all new and upgraded wastewater facilities to meet certain resiliency criteria for flood plains, storm surge, etc.

- State Resiliency Bonding creates a matching grant program through which municipalities could apply. The Open Space Land and Watershed Acquisition Grant (OSWA) is now open for applications where municipalities and nonprofit organizations can receive financial assistance to purchase open space. Additionally, $30M in climate resilience bonding was approved for FY22-23 to help fund adaptation and resilience programs and projects by municipalities, nonprofits, and academic institutions, including green infrastructure.

- EPA Healthy Communities Grant Program is New England’s main competitive grant program to work directly with communities to reduce environmental risks to protect and improve human health and the quality of life.

Foundations

- The Open Space Institute offers multiple grant opportunities for the coming year with a focus on supporting conservation on a permanent, landscape scale.

- The Kresge Foundation works both independently and in collaboration to award single and multi-year grants funding general operations, projects, and planning activities advancing strategic objectives in environment, health, community development, and other subjects.

- Arbor Day Foundation and TD Green Space Grants support green infrastructure development, tree planting, forestry stewardship, and community green space expansion.

Additional Income Sources

Taxes provide municipalities with the most consistent stream of income to fund both the implementation costs and the operation and maintenance costs associated with a nature-based approach. State and local governments across the United States have implemented different types of taxes to fund specific clean water and flood reduction strategies. Here are a few examples:

- Branford’s local Public Act No. 19-77 established Municipal Climate Change and Coastal Resiliency Funds, whereby a portion of tax revenues are set aside in an investment account to grow and match grants.

- The five towns on the east end of Long Island implemented the Peconic Bay Community Preservation Fund, a 2% tax on real estate transactions. The proceeds of this tax are directed towards open space preservation, water quality improvements, and projects that increase overall coastal resilience. Since its inception in 1998, the fund has raised over $1 B.

- In Iowa, a state Flood Mitigation Board relies in part on an incremental increase in the state sales tax to raise funds for flood mitigation projects. The board was created in 2013 and as of 2015 had approved nearly $600 M in projects.

- The nine counties of the greater San Francisco Bay area have established a $1/month parcel tax over the next 20 years to fund wetland restoration efforts to address the impacts of climate change and sea level rise. All told this will create $25 M a year for restoration activities, with a lifetime total of approximately $500 M to support the efforts of the San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority.

Municipal Success Stories

Low Impact Development and Green Infrastructure manage stormwater by using innovative strategies and nature-like solutions to slow the flow of runoff and protect water quality and habitats from development impacts. The Connecticut chapter of The Nature Conservancy has an interactive map that identifies several hundred resiliency projects in 33 towns, including natural and hard shoreline infrastructure and over 200 projects to address stormwater with a mix of hard and green infrastructure.

Rain gardens are a simple way to redirect polluted runoff from rooftops and other impervious surfaces back into the ground using a concave area filled with native plants.

This is one of over 200 bioswales installed in the right-of-way along streets in New Haven, CT. This type of green infrastructure contains native plants and a design engineered to capture a large volume of polluted runoff from roadways before it reaches storm drains.

You can find a host of examples by various organizations throughout Connecticut below:

Sunken Meadow State Park’s parking lots after green infrastructure retrofit, with restored marsh in front.

Some municipalities, as shown below, have complied with their clean water obligations and made significant strides and continue to work hand in hand with organizations such as NEMO and Save the Sound to protect Connecticut’s water bodies and reduce pollution impacts on habitat, fishing, and recreation.

Additional Resources for Municipalities

Several organizations have worked hard to provide detailed resources for municipalities to ease the path to permit compliance. They continue to update their content and expertise. Many can also suggest consultants and their own personnel to work hand in hand with municipalities. Please refer to these additional resources for guidance:

- Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (CT DEEP)

- Connecticut’s Conservation Districts serve municipalities and residents by providing technical services and education

- Eastern CT Stormwater Collaborative Presentation

- CT’s Updated MS4 Permit: Year 5 and Beyond

- Nemo CT MS4 Guide

Contact

For questions about this page or Save the Sound’s research, contact Brittany Chamberlin at outreach@savethesound.org.

For questions about the MS4 permit or general requirements, contact NEMO.