Something was off, though the imperfection would’ve been imperceptible to most people. Elena Colón took a long, last, critical look and suggested a correction to Lindsey Potts, who fine-tuned the final adjustment. They stepped back, reviewed their work, and were satisfied.

The freshly hung picture frame was straight and level.

Such attention to detail was to be expected, considering the nature of the document displayed inside the frame. It conferred that the John and Daria Barry Foundation Water Quality Lab had received certification by the Environmental Laboratory Approval Program (ELAP) of the New York State Department of Health-Wadsworth Center, an approved accrediting authority under the National Environmental Laboratory Accreditation Conference Institute. A lab doesn’t get ELAP-certified unless it has gone through a rigorous evaluation process of every aspect of its work: standard operating procedures, processing protocols, equipment maintenance, record keeping, and, of course, lab results, every bit of had it been scrutinized through paperwork submissions and in-person audits.

“This accreditation ensures there is heightened accuracy, reliability, and traceability in the data being produced in our lab,” said Elena, Save the Sound’s laboratory manager.

Securing ELAP certification was part of the plan before construction of a new Larchmont-based lab was underway. Elena started working toward that goal in early 2022, when the lab opened, and submitted the application last December. In August, Elena received notification that the lab was approved to process five analytes: fecal coliform, ammonia, nitrate-nitrite, orthophosphate, and phosphorus (a sixth analyte—E. coli—was approved last week). Now, the data generated through the processing of those analytes can now be accepted and utilized by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation when assessing whether specific waterbodies in New York are compliant with Clean Water Act standards.

Getting to this point required Elena, Lindsey, our laboratory technician, and director of water quality Peter Linderoth to work intensely to ensure everything adhered to ELAP’s exacting guidelines.

Literally, everything.

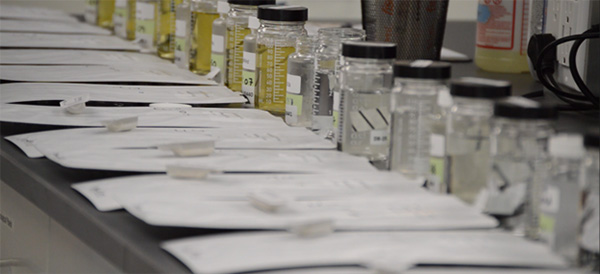

Take, for instance, the seemingly straight-forward process of bringing a water sample into the lab during our fecal bacteria monitoring season in the western Sound (there were more than 700 samples collected in the field during the 12-week 2024 season). Elena had to create updated chain of custody forms to record the date and time that a sample was delivered to the lab by a staff member or volunteer, who then signed that form. The sample water temperature had to be recorded in the lab whenever a sample was delivered. The device measuring the temperature must be calibrated quarterly and verified daily by a different thermometer that gets shipped to a certified vendor to be calibrated annually. All that just for getting one 100-milliliter sample bottle in the door, before anything can be processed, which requires its own set of paperwork and procedures.

The temperature in the freezer where samples are stored overnight needs to be checked daily and recorded. There are logs for tracking the result of the detergent residue testing to make sure there is no residue on any glassware after it’s been cleaned. These expanded quality control efforts can seem more intricate than the science being conducted in the laboratory. About the only piece of equipment that Elena does not have to be certified to use is the long-handled grabber she needs to reach the new binders, brimming with all the required paperwork, that are now stored on the top shelf of the cabinets around the lab (near the new filing cabinet, loaded with its own color-coded folders).

“We have always strived to produce high-integrity data in our lab. It’s remarkable how much more we’ve added to our record-keeping, our quality controls, and our procedural work going through this certification process,” said Peter. “This certification is a testament to our team’s commitment to our laboratory operations.”