Climate issues can be difficult to understand. This series is designed to deliver what you need to know about some of the most prevalent issues in climate policy today. In 1,000 words, let’s learn what ocean acidification means for Long Island Sound.

This article is written by Kaleigh Pitcher, a Policy Consultant at Save the Sound, working primarily in climate and environmental justice advocacy. She has a Master’s of Public Policy with a focus on Health and Social Policy from the University of Connecticut.

We’re used to hearing about climate change impacts like sea level rise, worsening storms, and increasing heat waves, but greenhouse gases can also cause changes at a chemical level—changes that are invisible but have a serious impact on Long Island Sound’s health.

What is Ocean Acidification?

Ocean acidification refers to the lowering of the water’s pH, and it’s primarily caused by an increase in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. According to the National Ocean Service, the ocean absorbs about 30% of the carbon dioxide that is released into the atmosphere. It then undergoes a series of chemical reactions that increase the concentration of hydrogen ions, rendering the water more acidic, which has disastrous effects on marine life. Acidification affects coastal water bodies as well, including wetlands, estuaries, and other waterways.

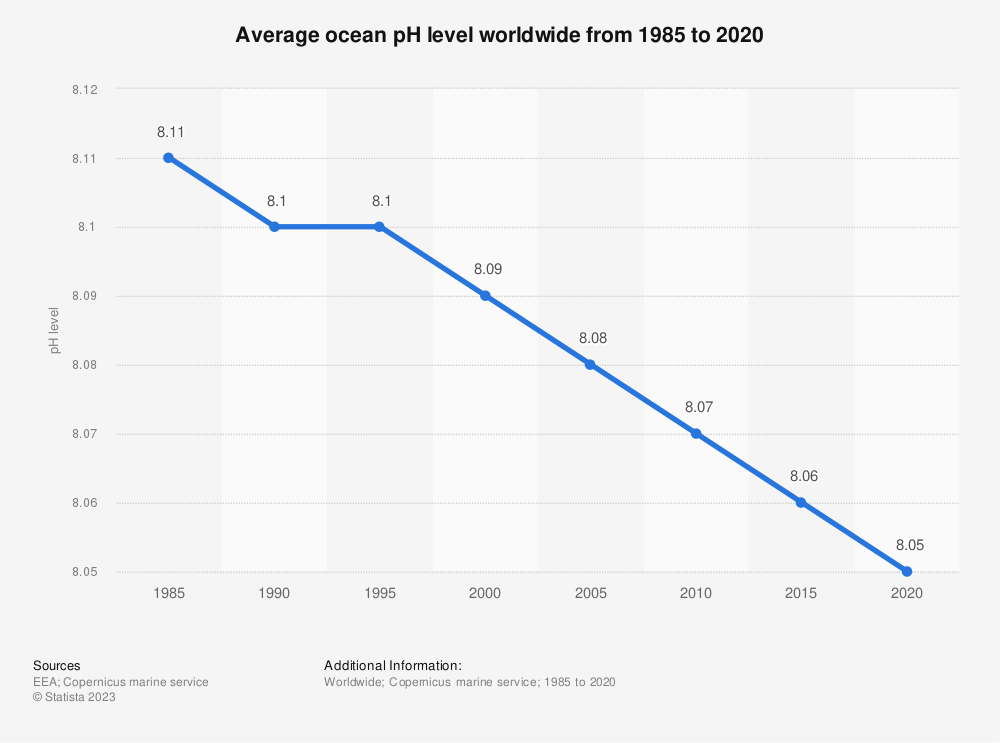

Acidification has been accelerated by human action. From 2008 to 2017, fossil fuel burning and land use changes were responsible for 40 billion tons of emissions each year. Presently, surface waters are 30% more acidic than their pre-industrial levels.

The effect of acidification depends on factors such as temperature and depth, with colder waters absorbing more carbon dioxide than warmer waters. Warmer waters can actually release carbon dioxide rather than absorb it. These warmer regions tend to have more stratification (layers of water with different characteristics), with surface waters saturated with carbon dioxide and unable to absorb any more, while deeper waters have less oxygen. Despite regional factors, acidification poses a threat to aquatic life at large.

Acidification in Long Island Sound

The pH of the ocean has decreased about 0.1 units from its pre-industrial levels. A lower pH indicates higher acidity. While the ocean on average has seen a 0.06 decrease since 1985, Long Island Sound has seen a 0.04 decrease per decade, according to UConn Marine Sciences. This means that the Sound is facing more rapid acidification than the global average.

Effects on Aquatic Life

Acidification has detrimental effects on marine life. An analysis of trawl catches in the Long Island Sound between 1996 and 2016 suggests a significant decrease in species diversity. Since 2000, crustacean and winter flounder populations have declined, in part due to the acidity of the waters. Both increasing water temperatures and acidity can stress marine life, making it more difficult for them to fight off disease and requiring more energy expenditure to keep them alive.

Higher pH waters also have fewer carbonate ions, which form the basis of many species that use calcium carbonate to build their shells and skeletons. The species cannot calcify properly, rendering them more vulnerable and inhibiting their growth. These species—including clams, snails, oysters, phytoplankton, and coral—typically form the lower levels of the food web, so these ecological disruptions are manifesting from the bottom up. The Long Island Sound Study notes that many fish species can suffer from stunted growth as a result of increased carbon dioxide and acidity. This directly affects their survival, and species were found to have lower rates of survival in more acidic waters. Given the rapidity of acidification, animals are unlikely to have a realistic opportunity to adapt.

Deoxygenation

Deoxygenation, or a decrease in oxygen, is associated with acidification. Cooler waters can hold more dissolved gases than warmer waters; when waters warm as a result of climate change, they hold less oxygen. The seawater then contains more dissolved carbon dioxide, making it more acidic.

Nutrients from runoff can combine with warming temperatures to make the situation worse. A UConn Marine Sciences study found that agricultural run-off is causing excessive nutrient inputs for microbial life in the coastal Long Island Sound region. This can cause eutrophication, where the environment is overenriched with nutrients.

According to Save the Sound’s Fish Biologist, Jon Vander Werff, “The influx of nutrients, often from sewage or fertilizer runoff, creates a rich environment for algae to grow. As the algae population booms, their respiration draws the dissolved oxygen right out of the water. These algal blooms can happen so fast that entire populations experience fish-kills.”

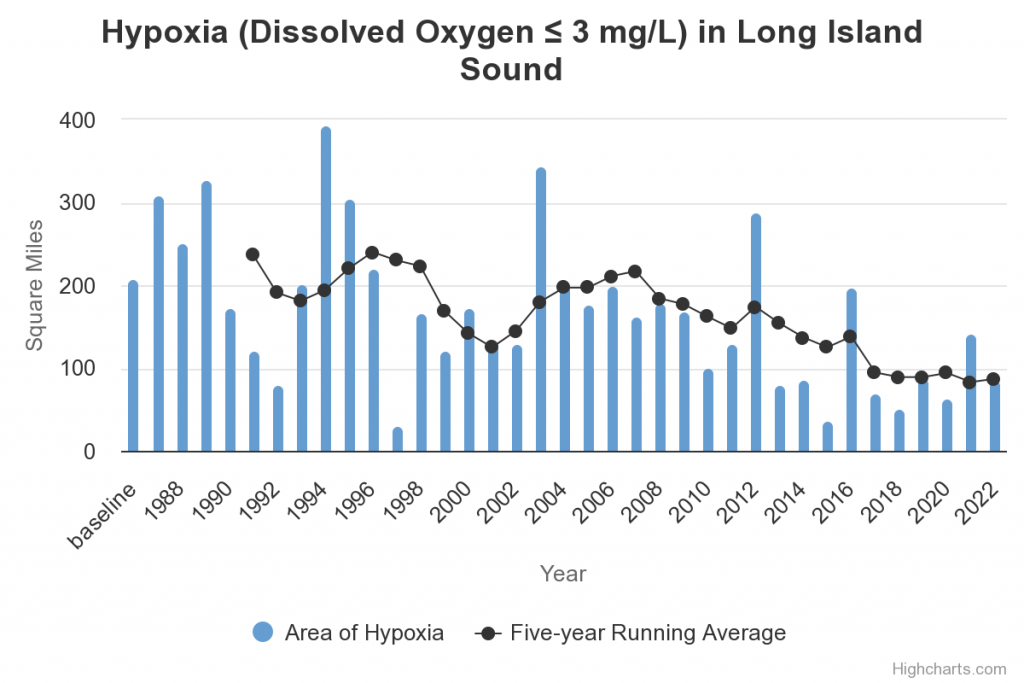

“Hypoxia [less than 3 milligrams of oxygen per liter of water] is a major concern when an excess of nitrogen and phosphorus enters an aquatic system. Dissolved oxygen levels in the water can become so low that the organisms who depend on their gills to use that oxygen (fish and invertebrates) will end up dying,” Vander Werff explained.

Connecticut’s Department of Energy and Environmental Protection performs a yearly monitoring of hypoxia in the Long Island Sound. Despite a general decline in square miles of affected water, in 2023, they found that a significant area of the Sound’s bottom waters has moderate, moderately severe, or severe hypoxia.

Mitigating Ocean and Coastal Acidification

The most obvious—and most difficult—solution to ocean acidification is drastically reducing the burning of fossil fuels. Emissions reduction would dramatically lower the threat of acidification at the source by reducing the amount of carbon dioxide entering our atmosphere and our oceans. There are also more localized efforts that can mitigate the effect in the Long Island Sound ecosystem.

Growing certain sea plants can help slow acidification by absorbing carbon dioxide and thus reducing acidity. Save the Sound has been at the forefront of eelgrass restoration in Long Island Sound; these plants consume carbon dioxide and protect shellfish. Eelgrass bed abundance is an indicator of good water quality and a hospitable environment for aquatic life.

Green infrastructure—rain gardens, permeable pavement, constructed wetlands, and more—is an invaluable tool for curtailing coastal acidification. While urban stormwater runoff and agricultural run–off can cause eutrophication, green infrastructure can interrupt the pollutants’ path. Investing in effective stormwater and drainage systems can ensure that untreated waste water doesn’t enter the Sound.

Ocean acidification is a worldwide issue, but it is also particularly local. Residents of the Long Island Sound region have the opportunity to support actions that can mitigate the effect of carbon dioxide in their coastal ecosystems. Explore Save the Sound’s projects to mitigate acidification, such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions, eelgrass restoration, legal actions on nitrogen pollution, and green infrastructure projects.