Climate issues can be difficult to understand. This series is designed to deliver you what you need to know about some of the most prevalent issues in climate policy today. In 1,000 words, let’s learn the foundations of climate advocacy in New York City.

This article is written by Kaleigh Pitcher, a Policy Consultant at Save the Sound, working primarily in climate and environmental justice advocacy. She has a Master’s of Public Policy with a focus on Health and Social Policy from the University of Connecticut.

September 17 to 24 marks the fourteenth annual Climate Week NYC. The event is hosted by the Climate Group in conjunction with the United Nations General Assembly, featuring key players in government, business, and advocacy to discuss global climate action. How did we get here? New York City has a storied history of climate action that goes back much further than 14 years—let’s take a look.

The Historic Need for Climate Advocacy

Climate advocacy as we envision it today emerged in the 1970s, as global warming became a salient issue and collective environmental action took off. But before that, New Yorkers were concerned about issues that still affect many of us today: water and air quality, green space, and protection from harmful materials. The Industrial Revolution in the latter half of the nineteenth century signaled a significant switch in New York’s economy. More than half of its population worked in manufacturing, trade, or transportation in 1910, three industries which greatly contributed to emissions. Due to rapid urbanization, the city soon became overcrowded with serious sanitation issues. Until 1895, 75% of solid waste was dumped directly into the ocean.

Proto-Climate Advocacy

With such extensive air and water pollution and so many residents watching, it is no surprise that New York became a hotbed of environmental advocacy. Public health advocates were calling in favor of advanced sanitation of the air, land, and water, with one New York Times reporter in 1871 scathingly denouncing those “responsible for the criminal neglect of the condition of this City.”

Numerous groups sprung up around this time; most notably, labor movements advocated in favor of more sanitary working conditions, and public health organizations fought for clean air and water. Together, they formed the crux of New York City social advocacy. In 1892, the City Club of New York was founded in part to provide for a clean water supply. They kicked off their inaugural year by recruiting protestors against the Departments of Health and Sanitation for inadequately performing their duties, which, the club leaders said, resulted in needless deaths. The public health aspect cannot be overstated. As a forerunner to the climate movement, public health advocates urged the municipality to use a scientific lens when forming policy. Health equity is also the basis of environmental justice.

The Dawn of the Climate Movement

In the post-industrial era, there was a broader emphasis on social action, and newspapers were quicker to report New Yorkers’ advocacy of their city’s natural environment. This includes beach pollution protests in 1925, relief projects by Bronx civic leaders in 1939, and protests against Hudson River pollution in 1944.

From the environmental movement of the mid-twentieth century came the climate movement. Concerned with changes in global climate, extreme weather patterns, and excessive emissions, the movement manifested itself primarily in cities, where the effects of air pollution were most evident.

In 1967, New York City was the most air polluted city in the country. This pronouncement came after the 1966 New York City Smog, a disaster that killed 168 residents. It was caused by a stagnant mass of air that covered the city, trapping its pollutants overhead. A report written shortly after wrote that the smog contained high concentrations of sulfur dioxide, which comes from the burning of fossil fuels.

In response to the smog, advocates in New York and beyond quickly took up the banner on climate action. The event served as a wake-up call to many Americans. President Lyndon Johnson soon signed the 1967 Air Quality Act, followed by the 1970 Clean Air Act signed by President Richard Nixon, in response to broader calls for climate action. With that, New Yorkers went into full force, from organizing hearings on pollution, reducing the level of incineration, and continuing to advocate for clean air. In one prescient action, the city threatened to sue auto-manufacturers for suppressing anti-pollution technologies—in 1969!

Modern Climate Action

Given New York’s diverse demography, residents of the city have been exceptionally active in the environmental justice movement, even when the city was less than amenable to their concerns. UPROSE was founded in 1966 in response to the environmental needs of the Sunset Park community in Brooklyn, but it has since grown to encompass public health and climate justice concerns. WE ACT was formed in 1988 in West Harlem by Vernice Miller-Travis, Peggy Shepard, and Chuck Sutton, who organized in response to a new sewage treatment plant in their community.

The United Nations is headquartered in Manhattan, granting the city and its residents significant opportunities for involvement in international climate action. In 1992, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change was hosted in both New York City and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The convention agreement stipulated that signatory governments must commit to reducing atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases. Article 6 also emphasized the need for advancing education, public participation, and international cooperation in the fight for climate change.

In 2012, the city faced another environmental disaster, Hurricane Sandy, which killed 44 New York City residents and displaced many more. All five boroughs were inundated with stormwater, causing flooding as deep as 8 feet. New York, as an island city, already has to contend with rising sea levels—climate scientists estimate an almost 2 foot rise by 2050. In response to the storm, New York City began to prioritize adaptation efforts such as climate resilient infrastructure (including park resiliency), greenspace, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions on a large scale. In 2014 the city’s government released New York City’s Roadmap to 80 x 50 (a reference to decreasing greenhouse gas emissions by 80% by 2050).

On September 21, 2014, New Yorkers congregated to form the largest climate march in history. Worldwide, over 600,000 people marched, with a staggering 311,000—just over 50%—of them marching in New York City. The event was organized by the People’s Climate Movement.

Renewable Rikers is a plan to use Rikers Island, New York City’s largest prison, for renewable energy, wastewater treatment, and other ecologically beneficial infrastructure projects once the jail facility is closed (the legal deadline is Aug. 31, 2027). Save the Sound is a member of the Renewable Rikers coalition, whose priorities include the environmental justice goal that “the island’s future uses benefit and respond to the wishes of the people and communities that have been harmed through its long, painful history.”

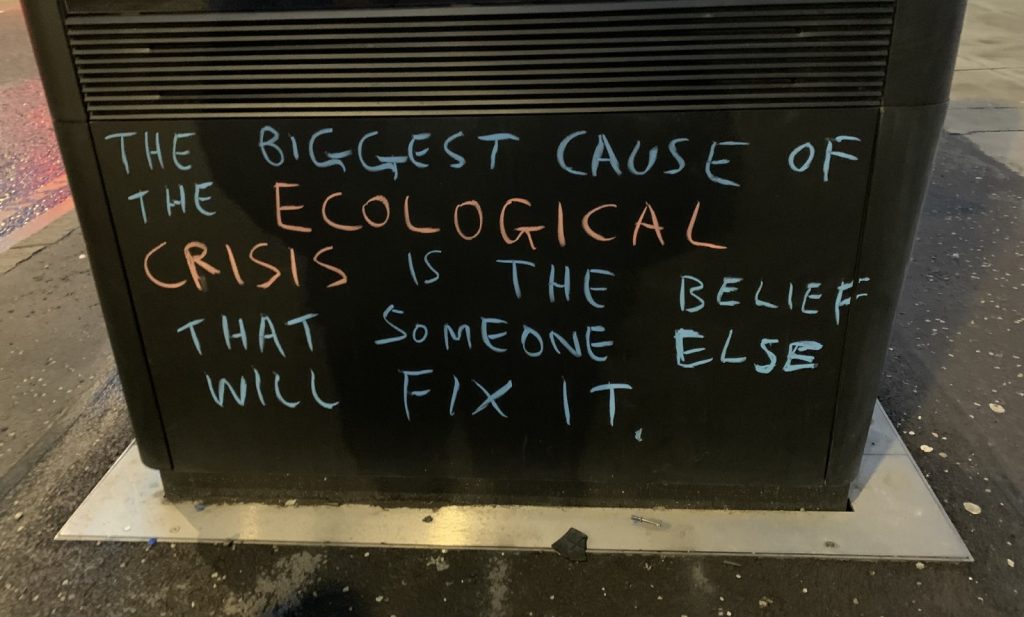

The city’s history of climate action shows just how resilient New Yorkers are. Climate advocacy is a collective action problem, which is why it’s so difficult to tackle—but New Yorkers have demonstrated that unity gets things done. Happy Climate Week, New York City!

For more information on Save the Sound’s New York City efforts, check out our website for ongoing projects including water quality legal actions, water quality monitoring, and Queens living shorelines. Earlier this year, we sat down with New York based activist Lea Melendez to hear about her climate advocacy, which you can read here.