For the end of National Water Quality Month, here’s deep dive into our longest-running water quality monitoring program, which completes its annual 12-week season on Sept. 1. Our field and laboratory staff, seasonal techs, interns, and 20+ community scientists collect water samples from 60+ sites in Westchester County, Queens, and Greenwich, CT, and analyze them in our John and Daria Barry Foundation Water Quality Lab in Larchmont, where we measure levels of fecal indicator bacteria in each weekly sample and then publish the results.

FLOWING

As with most journeys, this one ends with a dot on a map. Not a destination, in this case, but a designation. If the dot turns out green, all is well. Orange is a failure. Red dots are significant fails. When it comes to a journey of a water sample, you want to end up as a green dot.

The journey for what would become MR-0.24 in Week 9 of our 2023 bacteria monitoring program began not as a water sample but as simply water, flowing down the Mamaroneck River on a sunny summer Wednesday. Maybe it originated on the West Branch of the river, in the wetlands next to Archbishop Stepinac High School. Or maybe it came from the East Branch, up in north Harrison, 7.3 miles from the mouth of the river at Long Island Sound. Either way, this water would never reach the east basin of Mamaroneck Harbor. Less than a quarter-mile from its natural finish line, it would be intercepted by Scarlett Crakes.

SAMPLING

Scarlett’s journey began two miles away, down Boston Post Road, where at 9:32 a.m. in the supply room of Save the Sound’s Larchmont office, she pulled an orange folder from a plastic bin. She knew the folder was meant for her; on a blue tab, someone had written her name in black Sharpie, punctuated by a smiley face. Below that was a yellow tab that read: WED, AUG 9, 2023.

Inside the folder was a data sheet noting the four locations where Scarlett would be responsible for sampling on this day. There were three stops along Beaver Swamp Brook – one at Rye Neck High School, one a short hike (in waders) up a tributary that curls into the main stem of the brook, and one beneath a Route 1 bridge. The fourth was a rocky spot off Phillips Park Road on the Mamaroneck River. MR-0.24, as it was designated on the daily call sheet.

Scarlett, one of our two summer water quality interns, gathered her gear. There was an extendable pole with an eight-prong claw, a cooler bag with a shoulder strap, and a Ziploc bag containing another personalized handwritten note and accompanying smiley face (shout out to Quality Assurance protocols), five sets of blue rubber gloves, and five plastic specimen bottles, each labeled for one of the four sites, plus a spare. With a glance up at the tide chart on a white board, Scarlett headed out – halfway into the midday ebb tide.

Three stops and nearly two hours later, Scarlett pulled into the lot behind the movie theater and the shops and restaurants that feed the steady bustle along Mamaroneck Avenue. For the final time this morning, she removed her gear from the back of the car and headed off along a path down to the rocky riverbank. It’s a location few residents are aware of, though fast food detritus and a lost silver dragonfly charm indicated some recent visitors.

Scarlett arrived at the location at the bend in the path, indicated by coordinates on an info sheet in her folder: Longitude 73.732721, Latitude 40.951338. Sampling as close as possible to the precise spot as in previous weeks is essential to consistency of data. She placed her materials on the rocks, slid on her blue gloves, checked her phone, took out her black Sharpie, and wrote the exact time on the specimen bottle for this sampling station. It was 11:30 a.m.

She removed the plastic seal and unscrewed the cap, then placed it in the grip of that claw at the end of her pole. Scarlett extended the Go Go Gadget-style pole so that she could reach the river leaning forward from a safe spot on land, pivoted the bottle so that its mouth would be open in the direction of the oncoming current, and dipped it into the Mamaroneck River, causing a circle of ripples that looked like a thumbprint on the surface of the water.

At 11:31, 100 milliliters of water whose journey that morning had begun somewhere upstream were captured. Water Sample MR-0.24 had been secured.

Scarlett reclaimed the bottle from the claw, capped it, and placed it into the bag of ice with the samples from earlier in the day. Then she sat on the rocks, ungloved, removed the data sheet from the folder and documented current weather conditions (clear); the presence of odors, perhaps sewage, chlorine, decay, or something else (none); the presence of geese, ducks, racoons, rats, or other animals (none). On the back, she recorded other observations, specifically the trash she’d noticed in the area. All of these things could help explain the bacteria levels that may be present in this container of water.

By noon, MR-0.24 had been delivered to our water quality lab (even the chain of custody of every sample – who relinquished the bottle to the sampler; who received it – must be recorded on the form). The laboratory was set up to treat the samples, once everything collected from all the Wednesday locations were accounted for.

PREPARING

Work stations covered every available inch of countertop on the console in the center of the lab and along the far wall under the windows. Pouches were laid out in rows, each one labeled to match a sampling site. MR-0.24 was the sixth on the back table, along with other freshwater samples to be tested for E. coli. The samples from brackish waters would be tested for Enterococcus, different fecal indicator bacteria.

At 1:58 p.m., Scarlett retrieved MR-0.24 from a refrigerator and placed it in its designated station, next to another plastic bottle containing 90 mL of pure water. A pipette, preserved in its packaging, was placed next to a small packet of Colilert-18, a liquid culture which would help detect E. coli.

It took nine minutes for Scarlett to process the first five samples. Gloved up again, she removed the glass tube from its packaging, attached it to a white and blue pump handle, then placed it into the sample bottle. Squeezing the pump, she drew up 10 mL of MR-0.24 and expressed it into the pure water. Scarlett then emptied the contents from the Colilert-18 packet, the particles sinking into the water like flakes of fish food. Next, she took the new mixture – 90% pure water, 10% Mamaroneck River, seasoned with Colilert-18 – in her left hand, grabbed the next water sample in the row in her right, and slowly shook them both 25 times.

Sufficiently stirred up, the new concoction was then poured into the pouch. One side was covered with foil, the other was a series of clear wells – one big one at the top roughly the size of a takeout ketchup packet; then 48 square windows, each about the size of a thumbnail; and at the bottom, 48 little windows. This display case for water was placed in a rubber mold and then run through the Quanti-Tray Sealer Plus, forcing the treated water sample into each of the 97 wells and sealing everything in place.

Once all freshwater samples were processed, they were stacked and placed inside an incubator set to 35 degrees Celsius (95 Fahrenheit). Scarlett jotted the start time on a dry erase board mounted to the incubator door (14:28) and the time window the next day the samples would be ready for analyzing (8:28 – 12:28). E. coli needs to cook for 18 to 22 hours.

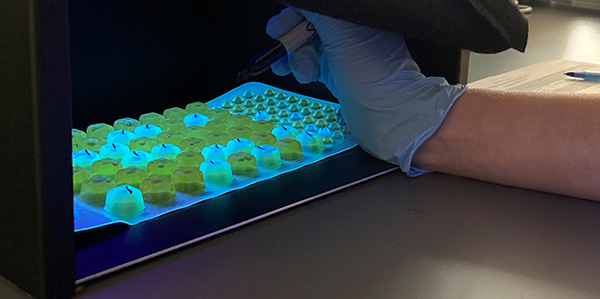

SCORING

MR-0.24 spent 20 hours, 10 minutes incubating until Heather Leonard, our other water quality intern, removed them for scoring. The water visible in every window glowed butterscotch yellow, as expected. The Colilert-18 feeds a variety of bacteria; to determine whether E. coli is present, Heather brings the MR-0.24 sample to the fluorescence analysis cabinet. She places the packet yellow-welled side up inside a chamber, shielded by a drape from the light in the room. She then looks through the scope at the top of the machine and views the windows under UV light. When she sees a cell fluorescing white, she marks them with a slash from a black Sharpie. Those wells are contaminated with E. coli.

Heather removed MR-0.24 from the cabinet to count its slashes: three among the small wells, 15 among the large. She then consulted the IDEZZ Quanti-Tray/2000 MPN Table, a grid of numbers that looks like an actuarial table. The top row is for small wells, the left-hand column is for larger wells. She finds the number at the appropriate intersection: 21.1.

Because only 10% of the sample was actually the water from the Mamaroneck River, you have to multiply that number from the chart by 10 to get the actual MPN/100ml – the Most Probable Number of colony-forming bacteria. MR-0.24’s score is entered onto a final data sheet: 211. In order for a freshwater sample to pass, the MPN per 100mL must be lower than 235.

MR-0.24 passed.

EVALUATING

Things don’t always fare so well for samples collected from the MR-0.24 location. It had passed the previous week, but it had failed each of the first seven weeks of the season, and it has failed the two weeks since. Scarlett’s three other samples from Aug. 9 all failed, with the sample from the tributary scoring nearly 5x the limit.

But on that day, at that time, at that spot, those 3.4 ounces fished out of the Mamaroneck River were safe for people and pets to swim in and interact with. When the Week 9 results were published in an interactive map on our website, MR-0.24 was depicted with a green dot. A happy ending.