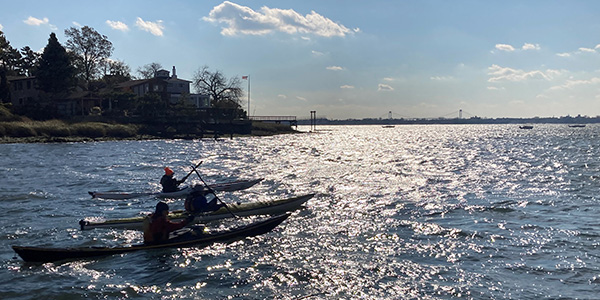

To those kayakers skimming across Eastchester Bay—City Island to one side, Rodman’s Neck jutting out from Pelham Bay Park on the other—it wouldn’t seem like such an outlandish idea. Nor would it to the paddleboarders putting in at Little Bay Park, setting off past the stone curtain of Fort Totten toward Bayside. And definitely not to anyone in a canoe flotilla, surrounded by the century-old trees of the Bronx River Forest, browsing the boundaries of the New York Botanical Gardens bound toward the American bison plains at the northern tip of the Bronx Zoo.

The people who already utilize New York City waterways as a playground would not dismiss the prospect of someday swimming in Westchester Creek or the East River as preposterous.

And you know what? Neither do we.

More than 50 years ago, the Clean Water Act established “a national goal that wherever attainable” the nation’s waters must be protected for fish, shellfish, and wildlife to propagate, and to provide for conditions suitable for “recreation in and on the water.” That standard—known in shorthand now as “fishable and swimmable”—was intended to be met by July 1, 1983.

Needless to say, that deadline passed unfulfilled, three weeks before Mr. Mom hit the theaters. Still, we are striving toward that goal, and our efforts most recently are focused on ensuring that the strongest-possible water quality standards are established for New York City waters.

Back in late March, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation proposed a series of updated regulations for saline waters statewide. This is the latest step in a process that began in 2017 when we, along with our partners Riverkeeper and NRDC, filed a lawsuit through the Pace Environmental Litigation Clinic asking to compel the EPA to adopt public health-based standards that would override DEC’s inadequate existing standards. Our suit was rooted in that Clean Water Act fishable, swimmable mandate, and it sought to address the massive problem of New York City’s sewer overflows, which result in 20 billion gallons of raw sewage entering coastal waters in all five boroughs. Every year.

Prompted by our pending case, the DEC opened a comment period last fall, seeking public feedback regarding its proposed new water quality standards. You may recall we asked you to fill out a survey that would help us demonstrate how New York City waters are being used for recreation (the mapping tool is still live and open for your input). That information helped us shape the joint comments we submitted with our partners, which DEC considered when issuing its recommended changes.

The good news is that we’re pleased with the standards proposed by DEC when it comes to defining what would constitute water safe enough for primary contact by users (swimming, or anything where you may become submerged in and potentially ingest the water), as well as secondary contact (kayaking, paddling, canoeing, etc.).

Where the proposed amendments fall short is in failing to apply the swimmable standards to all waterbodies. Some will be classified into categories that would set criteria below that level, rendering those waterways unswimmable for several decades to come without appropriate documentation and protections. We will be filing comments objecting to that component of the proposed standards, urging DEC and EPA to adhere to their Clean Water Act obligations.

Once we file those comments prior to the June 20 deadline, we’ll be asking for your help, too. Look for an action alert from us sometime in mid-June, which will enable you to add your voice to this important conversation. But there’s no need to wait that long to learn more about the proposed water quality standards. You can, for instance, attend a webinar on June 1 hosted by our partners at the SWIM Coalition; Peter Linderoth, our director of water quality, will participate in that informative discussion.

Water quality standards matter, but they won’t guarantee the waters of New York magically will become clean and safe enough for swimming. Those 20 billion gallons of sewage don’t care much for policy. A long, hard road lies ahead for us to achieve swimmable standards, but it can be done. It starts with the right rules and continues with an Olympian effort. Literally.

When you tune in for the opening ceremonies of the 2024 Summer Olympics, you’ll notice they will not be held in a stadium, as is tradition. Instead, the host city, Paris, will let the games begin with parade of barges down the Seine, showcasing the once-pollution-choked river that runs through the heart of the City of Lights. So much progress has been made in cleaning the river, it is expected that a couple of distance swimming events will be held in the Seine, along with the swimming portion of the Olympic triathlon.

If Parisians can take a plunge in a waterway that has been closed to swimmers for a full century, then perhaps the hope of someday swimming freestyle through Flushing Bay is not folly after all.