Tropical Storm Elsa made landfall in the Long Island Sound region in the early hours of Friday, July 9, dropping between 1.5 and 5 inches of rain on communities in New York and Connecticut in less than 12 hours. This resulted in coastal and inland flooding, road closures, rescues of several people from vehicles, and closed beaches. Sewage overflows totaled a minimum of 115 million gallons of raw and partially treated sewage entering the Sound and its waterways. As damaging as Elsa was, it could have been a lot worse—and this is exactly the type of storm we expect to see more of due climate change.

Below are reflections from experts across Save the Sound’s programs, offering diverse perspectives on the impact of Elsa through the lenses of their work.

Director of Water Quality Peter Linderoth

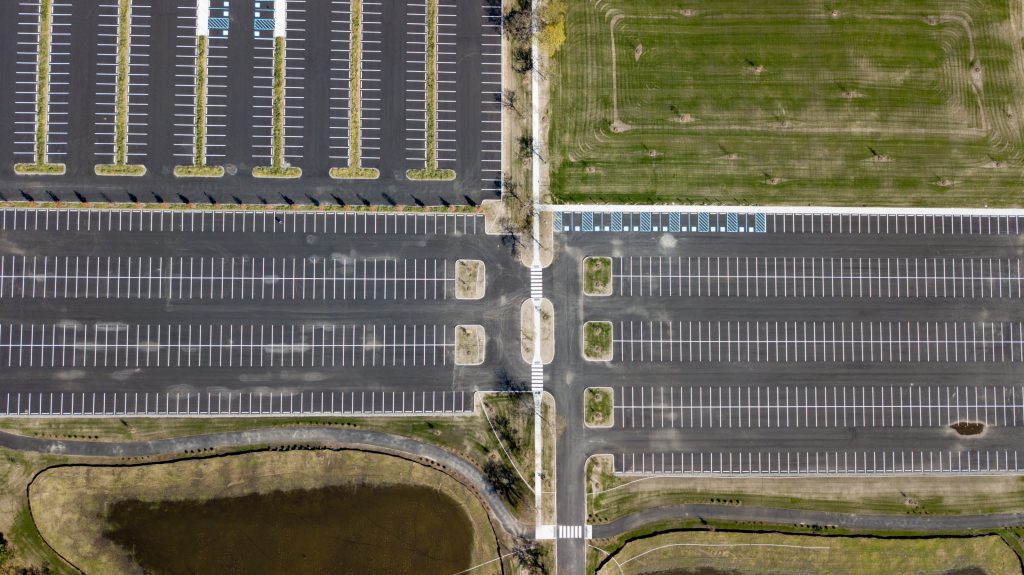

Tropical Storm Elsa brought an extraordinary volume of precipitation in a short time—over 5 inches of rain in 24 hours in Fairfield County! With all of that rain came extensive flooding and environmental impacts. Large volumes of stormwater flowed over impervious surfaces such as roads, roofs, and parking lots, making its way to Long Island Sound and its tributaries. Excess nitrogen and phosphorus from runoff contribute to depleted oxygen levels that suffocate aquatic life, while pathogens contaminate water and makes beaches unsafe for swimming and fishing. Elsa resulted in preemptive beach closures around the Sound due to beach management practices that close beaches for swimming after certain rainfall accumulations in a specified window. Numerous reports of sanitary sewer infrastructure failures which led to raw and partially untreated sewage entering our waters were also reported. As climate change continues to alter precipitation patterns to more intense and frequent storms, the Sound community will need to improve stormwater management, including infiltration and retention, to protect the health of our waters for people and aquatic life.

Climate & Energy Attorney Charles Rothenberger

The continued rise in global surface and water temperatures as a result of climate change means a longer tropical storm/hurricane season, with more frequent powerful storms. Coupled with increasing high heat days that make air conditioning more necessary, these storms are making ever more urgent the need to increase the resiliency of our electricity grid to protect communities from power outages. While the 13,000 Connecticut power outages reported from Elsa is far below the 720,000 created by Isais last August, the outages resulting from this relatively mild early storm are significant. Fortunately Connecticut has taken some steps to address the grid’s resilience. In the wake of Isaias, in addition to beefing up the distribution companies’ storm response efforts, the state legislature authorized an expanded microgrid program—which lets entities/areas generate their own power—to cover resilience projects and prioritizing projects in vulnerable communities. This past legislative session, Public Act 21-53 set a 1,000 MW target for battery storage deployment by 2030 and the CT Public Utilities Regulatory Authority recently issued a draft electric storage incentive plan to assist with the orderly development of a state-based electric storage industry. These efforts to enhance the resilience of the grid are an essential complement to the state’s emphasis on increasing the supply of clean renewable energy that will reduce our contribution to climatic warming.

New York Natural Areas Coordinator Louise Harrison

Thankfully, due to lower-than-anticipated winds, Tropical Storm Elsa had little storm surge effect on Long Island. Storm surge is a huge problem when it hits here. Much of Long Island’s electric service is above ground, so it’s easy to knock out power when there is a lot of wind, or when wind combines with heavy branches (such as when the leaves still are moist in spring or early summer, or when they’re snow-laden).

High water-table conditions can arise from high rainfall, especially near waterways; storm surge combined with that can cause severe flooding in some areas. Salt water moving into the coastal zones with surge lifts the groundwater and can cause septic failure and salt water intrusion into drinking water wells.

A high percentage of Suffolk County homes and businesses are serviced by old cesspools or by septic systems, which are only marginally better. When groundwater intercepts those systems because of storm surge, the groundwater becomes tainted. This, in turn, contaminates drinking water supplies or nearby waterways.

In addition to all the everyday benefits of naturally vegetated lands, they perform critical functions in the face of heavy rains, compared with hardened paved and rooftop surfaces, where rapid runoff can cause soil erosion and pollution of waterways. For instance, the soil of naturally vegetated steep slopes is held in place by the extensive, fibrous, root systems of trees and shrubs, acting like three-dimensional netting. Precipitation reaching fine root hairs can be absorbed, and rain is drawn downward into the soil or groundwater along the surface of older roots, which act as water conduits. These benefits accrue to people, wildlife, and water quality not only all around the Long Island Sound region but everywhere native ecosystems are left intact.

Assistant Soundkeeper Gavin Kreitman

Mass flooding events like the ones caused by Tropical Storm Elsa are becoming ever more frequent and are beginning to occur at earlier dates than previously seen. It’s imperative that water quality monitoring and watchdogging programs, such as the Soundkeeper, be more vigilant than ever in tracking down and eliminating all possible point sources of pollution. In doing so, we may be able to help mitigate the growing number of contaminants that are entering Long Island Sound through the runoff of unpredictable, climate-driven storms like Elsa. We need to reengineer the built landscape to soak up rainfall like a forest—this will knock down the peak flooding events to where they become less damaging and dangerous.

Assistant Director of Ecological Restoration Anthony Allen

Tropical Storm Elsa is exactly the sort of storm that highlights the connections among all the different types of projects we do on the Ecological Restoration team—and the scale of the work ahead of us. The good news is that we have the tools to mitigate the impacts of the next Elsa, and the one after that.

Living shorelines and wetland restoration provide an effective natural buffer to storm surge along our coasts and flooding in our rivers, while also providing critical habitat for threatened species. Removing derelict dams and replacing undersized culverts reduces the risk of infrastructure failure leading to road closures and loss of property or life, while securing the incredible benefits associated with free-flowing rivers. Thorough watershed planning and constructing the recommended green stormwater infrastructure projects can greatly reduce the polluted runoff that makes it into our rivers, which in turn keeps our waters safe and our beaches open. During this UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration our team will continue working to expand regional capacity, including our own, to complete this work.

The bottom line: climate change is not slowing down, so we have to accelerate our investment in nature-based resiliency for the sake of our most vulnerable habitats and communities.

Staff Attorney Kat Fiedler

Tropical Storm Elsa was yet another reminder of the urgency of our legal advocacy and enforcement on stormwater and municipal wastewater. Each time we have an event like this, massive amounts of sewage flow into our waters, requiring beaches to be closed. Municipalities are decades behind in routine maintenance and upgrades of aging or undersized infrastructure, and aren’t complying with basic requirements of their stormwater permits. Our legal enforcement actions require municipalities to make these overdue investments but municipalities are still failing to take this seriously, even as we face more frequent and larger storm events. We need to invest in systems now that can handle stormwater flows and infiltration, so that we don’t continue to pour raw sewage and other pollution into waterways used for swimming, subsistence fishing, and boating. These aggravated sewage spills will do the most harm in communities already suffering from environmental injustice and neglected infrastructure.

We know what we are going to face in the climate crisis, not just because of climate modeling but because the climate crisis is here. We know what we need to do. The legal team will continue to push for compliance with legal requirements that require adequate and resilient sewage and stormwater systems to protect healthy beaches and streams in light of the climate impacts we face.

Save the Sound President Curt Johnson: climate urgency and what we must do now

As I noted in my testimony in DC last month, the existential threat of climate change has become real health and ecological dangers this summer. Our towns reported that severe deluges from Elsa set off an eruption of a dangerous mix of 115 million gallons of raw sewage and polluted stormwater dumped into our rivers and into the Sound. As a visual: imagine Canada sending down two supertankers, the size of the Exxon Valdez, filled with a mix of raw sewage and polluted stormwater, and then dumping it into the Sound. That’s what 115 million gallons looks like. It would be an international incident, perhaps setting off a war—yet we did this to ourselves. Leaky pipes combined with the earliest named storm on record equates to climate disaster. We must tighten the pipes and fight climate change.

At the same time, tiny particles of soot from massive western wildfires are raising pollution levels to moderate and sometimes serious levels for air you breathe, threatening kids with asthma and anyone with a heart condition or COPD. It is making outdoor exercise dangerous.

Together we must support the Climate and Transportation Initiative and invest in offshore wind to lessen the climate pollution driving these disasters. Let’s use nature-based solutions to capture flood waters and protect our coastal communities from storms. Let’s fight to save this wonderful slice of this magnificent blue planet for ourselves and future generations.

(@LCVoters)

(@LCVoters)