The “Crab” We All Know and Love

Horseshoe crabs are often referred to as “living fossils” by evolutionary scientists, having remained nearly unchanged for 445 million years. Almost twice as old as the earliest dinosaurs, there are four species of horseshoe crabs still in existence today. While three of them are found only in Asia, the fourth — Limulus polyphemus — calls the east coast of North America its home. If you’ve spent any time on the shores of the Sound, you’ve probably seen them, or some old shells or molts washed up at the high tide line. Although they are called crabs, the lack of key features such as antennae suggests that they are not crabs at all. While they fill similar roles ecologically, they are evolutionarily more similar to arachnids like spiders and scorpions.

The most amazing phenomenon surrounding horseshoe crabs is how they breed. Horseshoe crabs congregate en masse on shallow, sandy beaches during spring high tides to spawn. The crabs do most of their courting during the three days around full or new moons. It’s an incredible sight to see, but this behavior makes them more susceptible to human harvesting and other predators such as raccoons.

Threats Facing Limulus polyphemus

The Atlantic horseshoe crab is considered vulnerable by the IUCN, with downward population trends linked to:

- breeding habitat fragmentation due to coastal development and harvesting,

- climatic changes,

- shifting predator populations,

- poor water quality,

- competition with invasive species, and

- human harvest for biomedical research

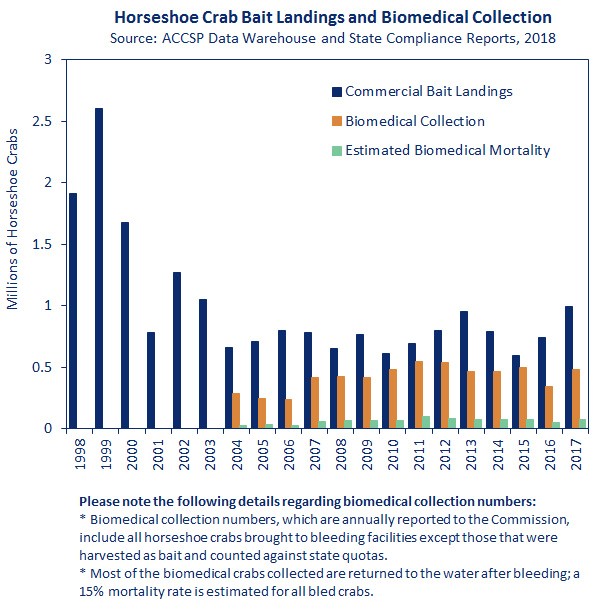

Historically, horseshoe crabs have been the preferred bait in the whelk and eel fisheries along the east coast. However, according to the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, after peaking in the late 1990s, the number of horseshoe crabs being harvested for bait has decreased.

Perhaps a more noteworthy use is the harvesting of horseshoe crabs by the medical industry to test the toxicity of vaccines. For this purpose, the crabs are bled and then returned to the environment, where 15% of them die as a result.

Defending the Future of Long Island Sound Horseshoe Crabs

There are three main population groups from the Yucatán Peninsula to Maine. Long Island Sound crabs are a subset of the Mid-Atlantic grouping, which runs from southern New Hampshire through North Carolina. Research from Project Limulus, based out of Sacred Heart University, shows that Long Island Sound’s horseshoe crab population is declining at a faster rate than the rest of the Mid-Atlantic stock. They have also demonstrated that many of the same crabs come back year after year to the same beaches to spawn. This trait can lead to local population depletion.

As scientists and legislators have become more aware of the population declines of the Atlantic horseshoe crab, some states have decided to take action. In Delaware, harvest of horseshoe crabs is limited to males so that the females have a chance to release their eggs. In New Jersey, there is an outright moratorium on all horseshoe crab harvests. Closer to home, New York closes the horseshoe crab fishery on either side of a changing lunar cycle during half of the breeding season.

The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission suggested both New York and Connecticut take state-level action to address the decline of the Atlantic horseshoe crab in the Long Island Sound. At a February 20 public meeting hosted by the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (CT DEEP), the following options for state action were presented:

- reducing annual harvest quotas,

- shortening the harvesting season,

- closing harvesting during spawning,

- ending horseshoe crab harvest altogether, or

- take no new action

Long Island Soundkeeper Bill Lucey sent a letter outlining Save the Sound’s position: supporting the option to close the harvest during spawning. On Long Island Sound we support closing the harvesting for the new and full moon periods during the two month spawning season.

This would be more restrictive than New York’s current legislation which closes the fishery for one new and one full moon. To be successful and equitable, there should be regulatory parity in New York and Connecticut waters. CTDEEP predicts this specific regulatory change would cut the harvest rate by ~50% which should result in a measurable population increase if harvesting is the leading factor in population decline.

While it’s important to protect horseshoe crabs as a resource, we must acknowledge their ecological importance as well. Horseshoe crabs release hundreds of thousands of eggs during spawning. Although a very small percentage reach reproductive age, these large numbers of eggs and spawn provide valuable nutrition to species such as the red knot and the Atlantic loggerhead turtle among many others along these species migratory routes. However, as Director of Project Limulus Jennifer Mattei said, “extinction is not the only way ecological links are broken.” This means we can reach tipping points where species populations become so low they no longer participate meaningfully as part of the local ecology, which weakens the whole system. This can result in ecological collapse, such as we saw with the Sound’s lobsters. We must act now to preserve horseshoe crabs as a resource as well as an important species that contributes to a healthy and vibrant Long Island Sound.

To learn more about Save the Sound’s work to protect local wildlife, Join Our Mailing List.