As we move into 2020 our members should reflect on two big victories achieved last year. The first would be the establishment of a 12-mile no fishing buffer off of the Coast of New England that prohibits trawling for Atlantic Herring. This management decision protected a large portion of the area outside the place where our remnant river herring stocks “stage” prior to entering the Sound to run up our rivers to spawn. The second victory was the establishment of a moratorium on the Atlantic Menhaden Fishery in response to Omega Protein LLC’s overfishing its quota in Chesapeake Bay. Thanks to hundreds of comments from all of you, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, the Federal Fishery Management Councils, and the nine bi-partisan governors that signed a letter demanding a moratorium on menhaden harvest we held a powerful industry to account.

Atlantic herring and menhaden along with the river herring harvested as bycatch in the trawl fishery are all considered forage fish.

Forage Fish in the Food Web

Forage fish are a key component of the marine ecosystem which is based on “primary productivity” the process by which sunlight and nutrients are converted into phytoplankton. This phytoplankton feeds forage fish directly and indirectly through zooplankton. This in turn creates a massive transfer of nutrients and sunlight into vast schools of herring which feed hundreds of species including us.

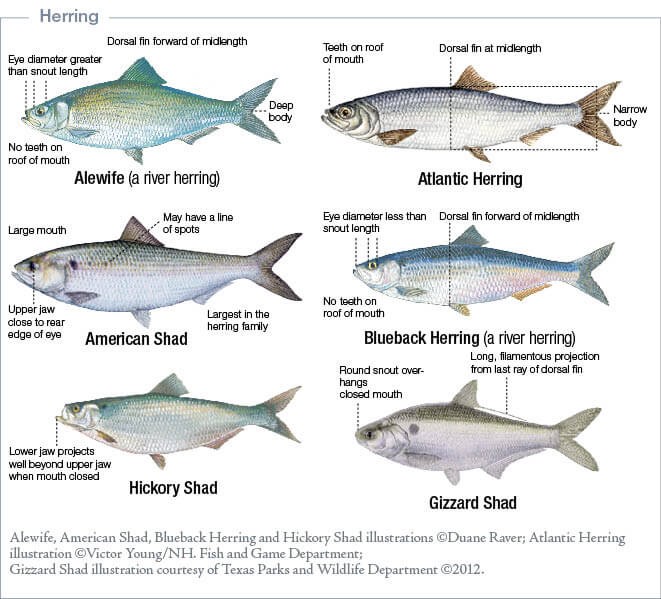

We have several types of herring in Long Island Sound; the entirely marine species; Atlantic herring and menhaden, as well as the freshwater-spawning species, such as alewives, blue back herring, and the three shad species; American, gizzard, and hickory.

With the exception of menhaden and a few healthy river herring runs, all of our herring stocks are at historically low abundance for the past three decades as illustrated in the graph below.

While in the case of menhaden the current population is healthy, targeting specific areas can lead to local depletion which can impact an array of species from seabirds to predatory fish and marine mammals. Predators will move from an area depleted of food impacting fishing, whale watching and, in the case of some birds, nesting success.

Climate and Forage Fish Population Variability

Natural fluctuations in forage fish are normal since they are dependent on plankton for food and ocean currents for larval dispersion. Climate variation, both annually and within the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) change ocean circulation patterns and water conditions such as salinity, acidity and temperature change plankton abundance, diversity and location. These changes can have massive effects on larval success and food availability, naturally causing wide swings in population abundance.

Prior to the industrial age, these swings occurred regularly resulting in seabird die-offs and variations in marine mammal and predatory fish populations. However, given the descriptions from early explorers and oral history from the First Nations it is obvious that there was a baseline of vast abundance that no longer exists. These earlier fish populations had enough elasticity to quickly absorb short-term ecosystem changes and bounce back quickly. A sampling of good books looking at historic abundance include “The Founding Fish” by John McPhee, “Running Silver” by John Waldman and “The Most Important Fish in the Sea” by H. Bruce Franklin.

Times have changed quickly. We now face a downward pressure on some of our fish populations that show signs of chronic depletion as depicted in the river herring graph. Even given decadal climate patterns, we should not see multi-year numbers near zero.

Over the course of just a few hundred years, humans have altered the watersheds with dams, sewage, fertilizer, toxic discharges, air pollution, and concrete. Fishing fleets transitioned from subsistence-based to highly industrialized harvesting techniques powered by diesel and hydraulics. On top of this, we are recording rising sea temperatures and lowering pH. Species are moving, our commercial fishing fleets are hurting, and recreational opportunities are dropping. We need to respond quickly.

To bring back our fish productivity it is necessary to institute habitat restoration and fishery management on a wide-scale. Within the watersheds we must remove all non-essential dams, restore natural river and floodplain function, modernize our sewage treatment options, leave fertilizer applications to farmers producing food, reduce the amount of impervious surfaces, electrify transportation to stop exhaust settling on the waters, and re-green our cities to capture polluted stormwater runoff and bring vibrancy into impoverished neighborhoods.

Fisheries management is the other factor within our control. As of this writing there was a public hearing on the Forage Fish Conservation Act (H.R. 2236) in the House Natural Resources Committee at the federal level. All people interested in fish and wildlife should follow this bill closely.

Commercial fishing is a vital part of the nation’s food supply. We want a healthy and prosperous fishing fleet to provide high quality food to our people. What we don’t need is maximized pressure on the base of our aquatic food chain for industrial purposes. Fishermen need bait so bait fisheries are necessary. Eating forage fish such as sardines, herring and anchovies are an excellent way to eat lower down on the food chain and still get the benefits of seafood.

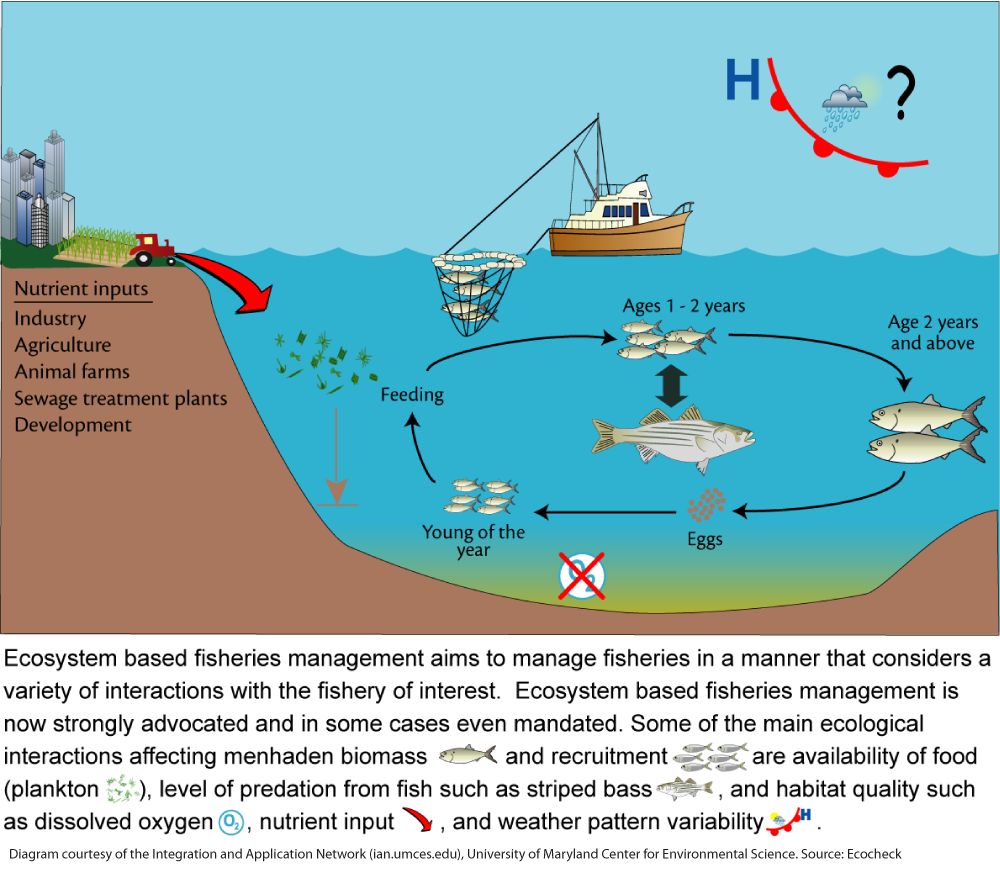

Biological Reference Points and Ecosystem Based Fisheries Management

Ecosystem Based Fisheries Management is a relatively new concept in fisheries management and there are few examples of its implementation. However, during the first week of February 2020, the ASMFC is considering whether to vote on providing a Biological Reference Point (ERP) for striped bass within the menhaden fishery. This means that the fishing industry sectors will get a share of the total menhaden biomass to harvest, the biomass itself will be protected at a level that provides ample spawning production, and striped bass will get some of the quota set aside for their species as a direct consideration. There are those that fear this style of management will create a future where humans are cut out of the allocation. However, if it works as intended it should provide a greater long-term abundance. On those years that the AMO reduces the menhaden population it is true that there may be less fishing opportunity, but providing for the other species that consume menhaden increases the overall fishing opportunities while supporting other species in years of low abundance.

As a salmon gillnetter friend of mine once said during a particularly poor fishing season; “If I don’t make enough money to take the winter off, I’ll just find something else to do”. That’s how life is for all people and animals trying to make a living from the natural world. There is never a guaranteed paycheck.

Key Takeaways

Addressing carbon pollution, repairing our watersheds, and factoring in ecosystem values of forage fish in management decisions can help bring back past abundance of forage fish. This abundance will in turn provide a more secure future for other fish and wildlife species coupled with our own subsistence, recreational, and commercial fisheries.

Therefore, it is vitally important for all of us to keep an eye on policy makers to ensure they keep moving things in the right direction. This means watching every water law, fishery management plan, and land-use decision to ensure we are creating the conditions for a fish filled future.

Bill Lucey, Long Island Soundkeeper