Back in the 1990s and early 2000s, movies like A Civil Action and Erin Brockovich sparked public conversations about the far-reaching and long-lasting impact of polluted land and groundwater. We’ve all heard stories about the battles to assign accountability for contaminated groundwater, but what about the stories of recovering and restoring the affected land and water?

For four decades, CFE and Save the Sound have fought at the forefront of Connecticut’s land, air, and water battles. Not only do we win battles to ensure accountability, we lead projects to restore injured natural resources. The history of our relationship with the Quinnipiac River paints a full picture of what it takes to restore contaminated land and water, from hazardous waste dump sites to court rooms and, eventually, removing decrepit dams and adding native plants.

***

The Old Southington Landfill opened in the 1920s and remained in operation up until 1967, at which point it was closed, covered, and seeded with grasses. According to state records, dumping of hazardous wastes began at the site in 1950, and in 1979, groundwater sampling revealed contamination of a nearby public water supply well. The town of Southington closed the well, but the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) designated the former landfill as a site of significant environmental concern and contamination.

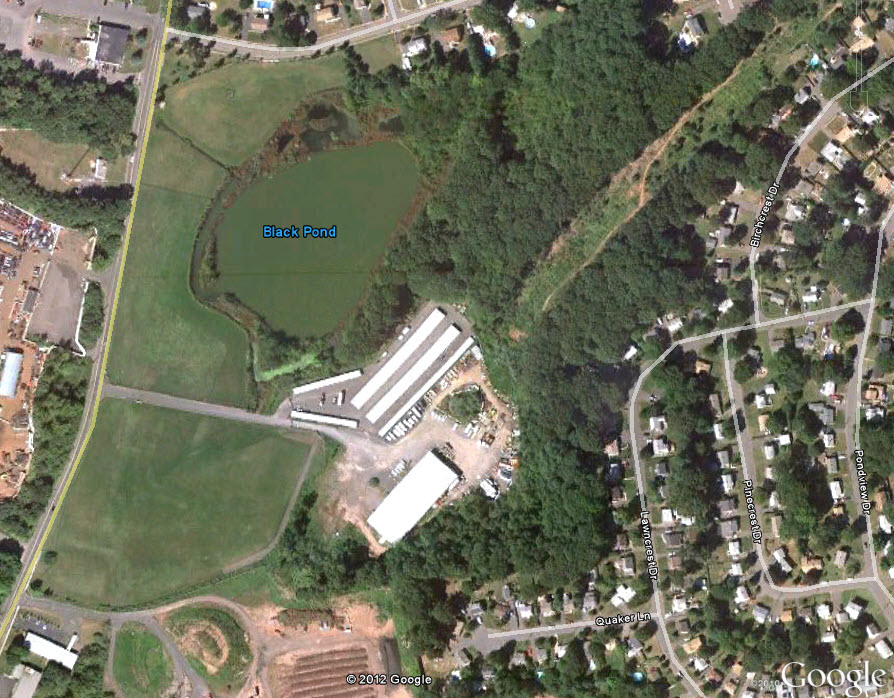

In 1984, 11 acres within the Quinnipiac River Basin were designated as the Old Southington Landfill “Superfund” site, a special title assigned by the EPA to areas polluted by hazardous contaminants causing significant environmental emergencies. Mercury, cadmium, and other contaminates were discovered in water and sediment of an on-site pond – Black Pond – which connects by stream to the Quinnipiac River. According to the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP), “Solvents, oils, petroleum hydrocarbons, chemical and liquid sludge, chemical solids, and other wastes were deposited above and below the water table in wetland and non-wetland areas just west of Black Pond.”

Additionally, a hazardous waste treatment facility called the Solvents Recovery Service of New England operated in Southington between 1955 and 1991, during which “faulty operating practices resulted in significant contamination of the land, groundwater, and air,” according to DEEP. The land occupied by the Solvents Recovery Service was also designated as a Superfund site in the 1980s.

According to the U.S. Department of the Interior, additional wetlands at the Old Southington Landfill Superfund site were destroyed “during remedial activities adversely affecting aquatic organisms and migratory birds.”

***

We joined the EPA’s legal battle against the polluters, and we continue to work with both state and federal agencies on habitat and groundwater restoration efforts. While the state controls funding for groundwater replenishment, the federal government controls funding for wildlife habitat restoration.

In 2009, then-state Attorney General Richard Blumenthal announced $2.7 million in funding for cleanup of the landfill site. In response, CFE proposed projects to filter rainwater as it fell on the land around the Quinnipiac River, allowing it to recharge contaminated groundwater. In 2011, CFE received $415,000 in grant funding through the Quinnipiac River Groundwater Natural Resources Fund to be used in collaboration with local and national organizations for replenishing groundwater lost to contamination.

Our efforts to restore groundwater recharge areas include the construction of nine residential and two commercial-scale rain gardens in the Quinnipiac River Regional Basin. Rain gardens, shallow depressions planted with water-loving native plants, collect and absorb stormwater runoff from nonporous surfaces like driveways, parking lots, and sidewalks. The collected waters are filtered through the rain garden’s soil and can more easily replenish groundwater, rather than being lost to storm drains. This also helps prevent neighborhood flooding and pollution of Long Island Sound by runoff. You can read more about the benefits of rain gardens on our site ReduceRunoff.org, and about the rain garden projects here.

Back in 2012, CFE/Save the Sound completed the installation of a fishway at Wallace Dam in the Quinnipiac River with funding from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, Connecticut DEEP, Restore America’s Estuaries, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Fishways are installed at waterway barriers, like dams, to enable the migration of fish. The Harry Haakonsen fishway, named for the former Southern Connecticut State University professor known for his research on the migratory behaviors of Atlantic salmon, opened 17.3 miles of river and 171 acres of lake and pond habitat to migratory fish foraging and spawning.

In 2013, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced $800,000 in settlement funding from both contaminated Southington sites for river restoration, recreation, and education projects. Our proposals to remove dams and restore wildlife habitat lost or damaged by the contaminated water were accepted, and our work to restore and improve the Quinnipiac River is ongoing.

***

As of August 2016, CFE/Save the Sound has executed 18 successful river restoration projects, including the removal of dams and revitalization of riverbanks to revive habitat for wildlife.

While our efforts for habitat restoration benefit fish and wildlife, the removal of dams also makes these rivers accessible for their human neighbors to kayak, fish, or wade in and lets residents observe the amazing power of an ecosystem to recover. In August 2016 alone we removed two dams from the upper Quinnipiac River, freeing miles of Connecticut rivers and opening the way for fish to swim upstream and safely spawn. Vital fish species like American shad and river herring can now access their ancient spawning grounds for the first time in more than a century.

“Opening up the Upper Quinnipiac is a big step in our campaign for free and clean rivers,” said Gwen Macdonald, director of habitat restoration at CFE/Save the Sound. “Free-flowing rivers open up the habitat needed to bring back an abundance of fish and wildlife to Long Island Sound and our rivers. Over the last decade, we’ve partnered with federal, state, and local governments and hundreds of volunteers to restore 80 miles of river around the Sound so herring, shad, and eels can reach their native breeding grounds. And free rivers are safe rivers—when an old, decrepit dam comes down, surrounding communities aren’t as threatened by flooding and families can enjoy kayaking and wading.”

Our upcoming plans to continue improving the Quinnipiac River for its human and wildlife beneficiaries include the removal of an exposed, unused water line that crosses the river in Cheshire. This will open a pathway for a canoe and kayaking trail from Southington to Meriden.

Humans caused the problem, but we are also the solution. While humans are responsible for the damage done to the Quinnipiac River Watershed so many years ago, together we have helped restore vibrant life to the river. Witnessing this ecosystem’s power to recover is inspiration for everyone working to restore and protect our land, air, and water.