Part 2 of a two-part series on Plum Island by John Turner of the Preserve Plum Island Coalition. Here’s part 1.

The number of bird species that have been found on Plum Island is quite surprising. For the past six or seven years researchers have been conducting monthly bird censuses on the Island and, as of this writing, 220 species have been detected here, approximately 1/4 of all the bird species found on the North American continent! These include the federally endangered roseate tern, federally threatened piping plover, many osprey nests, and a variety of migratory and nesting song birds.

I vividly remember watching a pair of American oystercatchers on the beach in the southwestern corner of the Island. What a sight they were with bright red bills, yellow eyes, and loud raucous calls as they flew about in unison, devotedly focused on each other in courtship.

Perhaps the biggest surprise I’ve encountered at Plum Island took place while touring its eastern tip in early spring. There amidst the many rocks immediately offshore were dozens of lazing harbor seals. While scanning the group more closely, I noticed a few seals with more elongated snouts and heads a bit like a horse—these were grey seals—the harbor seal’s bigger cousin. Later, I would learn the eastern end of Plum Island comprises the largest seal haul-out site in southern New England, containing as many as 600 seals during some winters.

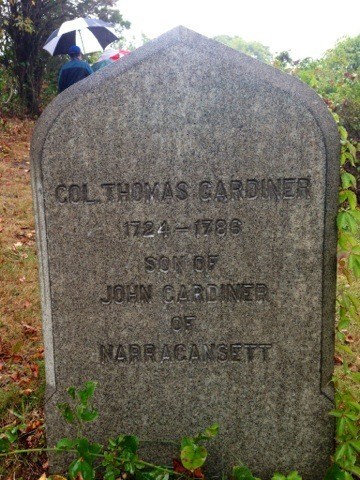

On my most recent trip to the island, I had the chance to visit the gravesite of the only soul to be buried on Plum Island, that of Colonel Thomas Gardiner. He supposedly died of smallpox in 1786 at the age of 62, and nobody wanted to be involved in the burial for fear of contracting the infectious disease. He was unceremoniously laid to rest not far from the manor house in which he lived, which is situated a little west of today’s laboratory building.

On my most recent trip to the island, I had the chance to visit the gravesite of the only soul to be buried on Plum Island, that of Colonel Thomas Gardiner. He supposedly died of smallpox in 1786 at the age of 62, and nobody wanted to be involved in the burial for fear of contracting the infectious disease. He was unceremoniously laid to rest not far from the manor house in which he lived, which is situated a little west of today’s laboratory building.

While looking beyond the gravesite, the last surprise of the Island was revealed to me. Approximately 125 feet southwest of the headstone, I noticed a remarkably large, white oak tree with a branch spread of at least 50 feet. From a distance, the main trunk appeared to be 8 to 10 feet in circumference. A tree of this stature belies the fact that at one time, just like with the large Atlantic white cedar trees once found here, Plum Island was vegetated by some old growth timber.

Plum Island undoubtedly has many more surprises to offer up. It is the hope of the Preserve Plum Island Coalition that Congress will pass the legislation to stop the sale of the Island, and dedicate it as a national wildlife refuge, park or preserve. Then, all Americans will have the opportunity to enjoy her many surprises for future generations to come.

John Turner is the spokesperson for the Preserve Plum Island Coalition. He also currently serves as the Open Space Program Coordinator for the Town of Brookhaven, overseeing the Town’s open space and farmland acquisition program. Prior to this, he served as Director of the Division of Environmental Protection of the Town of Brookhaven, a position he gained after serving as Director of Conservation Programs of the Long Island Chapter of The Nature Conservancy. He also serves in a part-time capacity with the Seatuck Environmental Association where he serves as a Conservation Policy Advocate working on a variety of water quality and wildlife related issues.

Where’s the link to the first part of the article?

Part I of the article: https://greencitiesbluewaters.wordpress.com/2015/10/28/an-island-full-of-surprises/