Part two looks at which of Connecticut’s coastal communities struggle with flooding damage, what it’s costing us, and how we can improve the situation. Read part one here.

There are 12,000 “severe repetitive loss” properties covered under the floundering National Flood Insurance Program. 260 of them are in Connecticut, the most of any New England state. And according to a recent article by the New England Center for Investigative Reporting, Milford and East Haven have the largest share: 36 homes in Milford and 29 in East Haven have been banged up again and again to the tune of $14 million in losses since 1980.

The hardest-hit neighborhoods in these towns are built on small barrier beaches, unstable strips of dunes and grasses that separate tidal marshes from open water. When allowed to exist naturally, barrier beaches are some of the most dynamic coastal environments. They grow, migrate, shift, erode, and retreat over time. Barrier beaches are stunningly beautiful places to visit, but stunningly poor places to build communities. The beaches want to move, we want to stay.

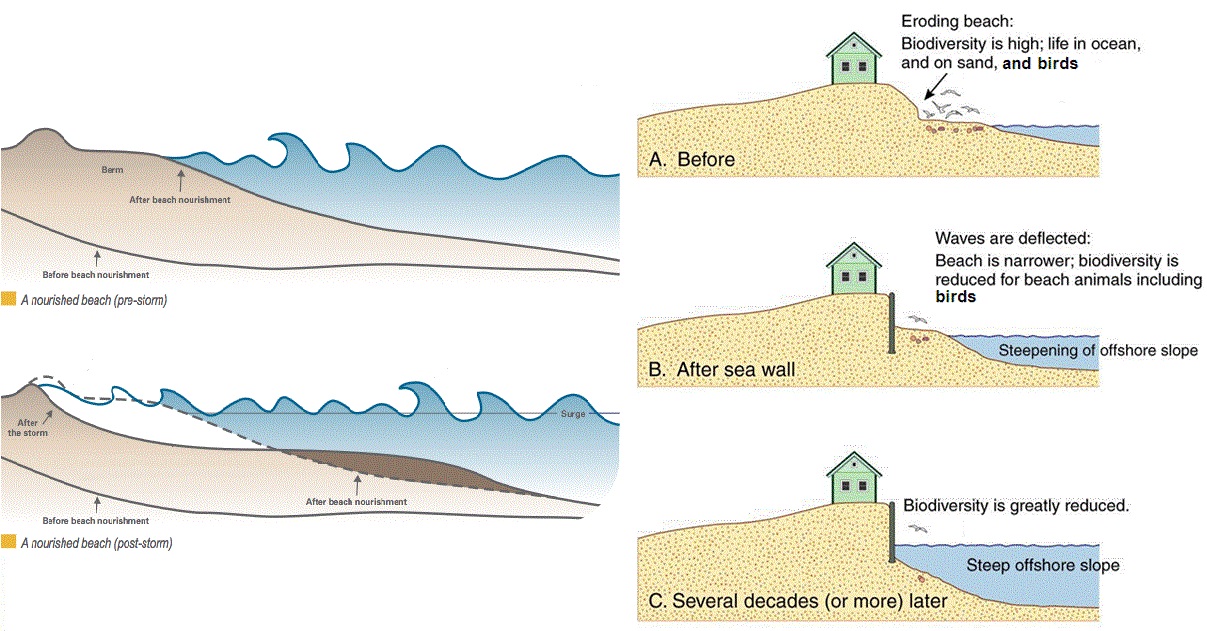

In order to maintain some consistency on barrier beaches, we often resort to redesigning the shoreline. Beach nourishment programs widen the coast, but only temporarily. Eventually erosion will take the sand away, and adding more season after season is expensive and repetitive. Coastal armoring like seawalls or bulkheads are unnatural and environmentally-destructive. They accelerate erosion on the beaches in front of them, and can collapse during large storms. And all these actions are backed by a failing flood insurance program.

This is clearly unsustainable, and has been for some time. With the increased potential for flooding thanks to climate change, and NFIP in debt $24 billion, there must be a better way forward.

In recent years, major coastal cities like Boston, New York, and San Francisco have put forth practical ideas to improve coastal adaptation and resiliency. The usual suggestions fall into two of three general categories: protection (seawalls, breakwaters, riprap) and adaptation (raised structures on stilts, flood proofing below-ground and first floors). In Connecticut, there’s a proposed bill to invest almost $25 million in various adaptation methods. But overall, there does not seem to be much support for what could arguably be the most meaningful and effective method—retreat.

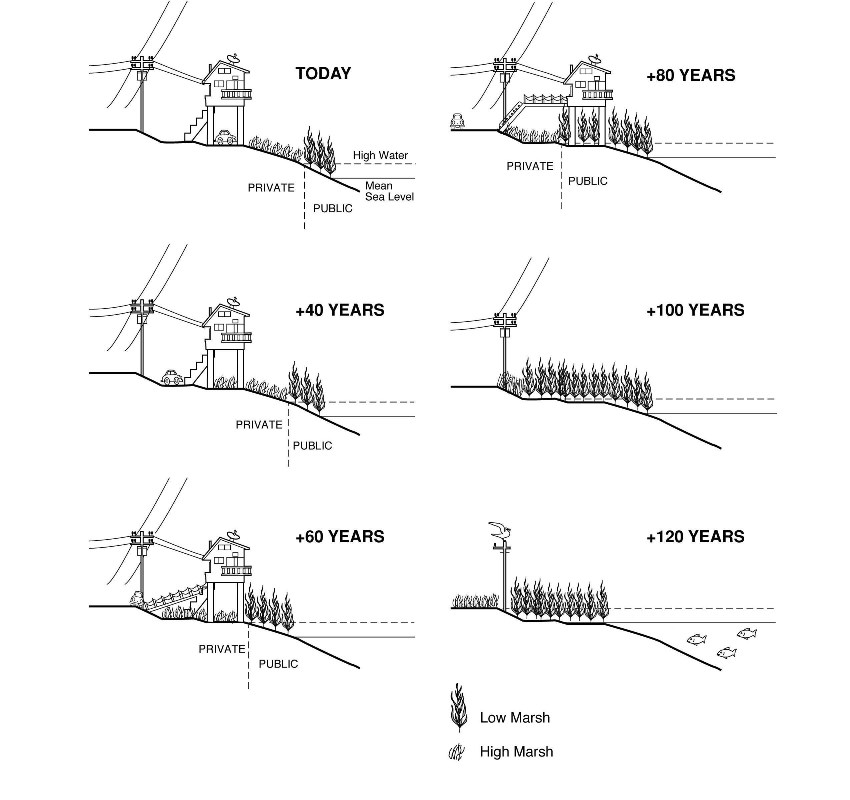

For some areas, especially in cities, retreat may not be an option. But there are many coastal communities such as Milford or East Haven, where we have opportunities for measured retreat that would gradually move shoreline development inland through buy-outs and rolling easements.

It makes sense to create an easier way to buy people out of their destroyed properties than to continually rebuild. But the process is just the opposite. It is very disheartening to see tax and insurance policies, lack of leadership in the states, and FEMA bureaucracy effectively keeping voluntary buy-outs off the table as a realistic strategy.

Buy-outs have been used before, just not for coastal flooding. The Town of Plainville is in the process of buying and razing flood-damaged homes along a tributary of the Farmington River. Their plan is to transition the land into beautiful riverfront open space.

Along our coasts, buy-out programs could be coupled with such a commitment to invest in and expand public access—access that would benefit everyone.

Imagine a coastline of beautiful seaside parks and forests, open for our enjoyment, and free to function naturally. We’d have dunes and sand bars naturally replenishing our beaches and building coastal habitats. We’d have coastal wetlands and marshes absorbing flood waters and protecting our communities above the flood plain. We’d have coastal forests dissipating strong storm winds and helping shield our homes from destruction.

And, most importantly, we wouldn’t need the National Flood Insurance Program. It was a bad idea at the start, and trying to keep the NFIP would only cost us more in the future—more property, more taxpayer dollars, and more lives.

Maybe it’s time for a change. As one expert points out, “Unbuilding hazardous shoreline communities is now a fantasy—but rebuilding over and again is madness.”

Posted by Tyler Archer, Outreach & Development Associate for CFE & Save the Sound.

2 thoughts on “Faulty Flood Insurance leaves Coastal Communities in Over Their Heads (Part 2)”

Comments are closed.