Water quality in Long Island Sound was bad during the summer of 2012, after a number of years when conditions were not so terrible.

The question is why. What was different about 2012?

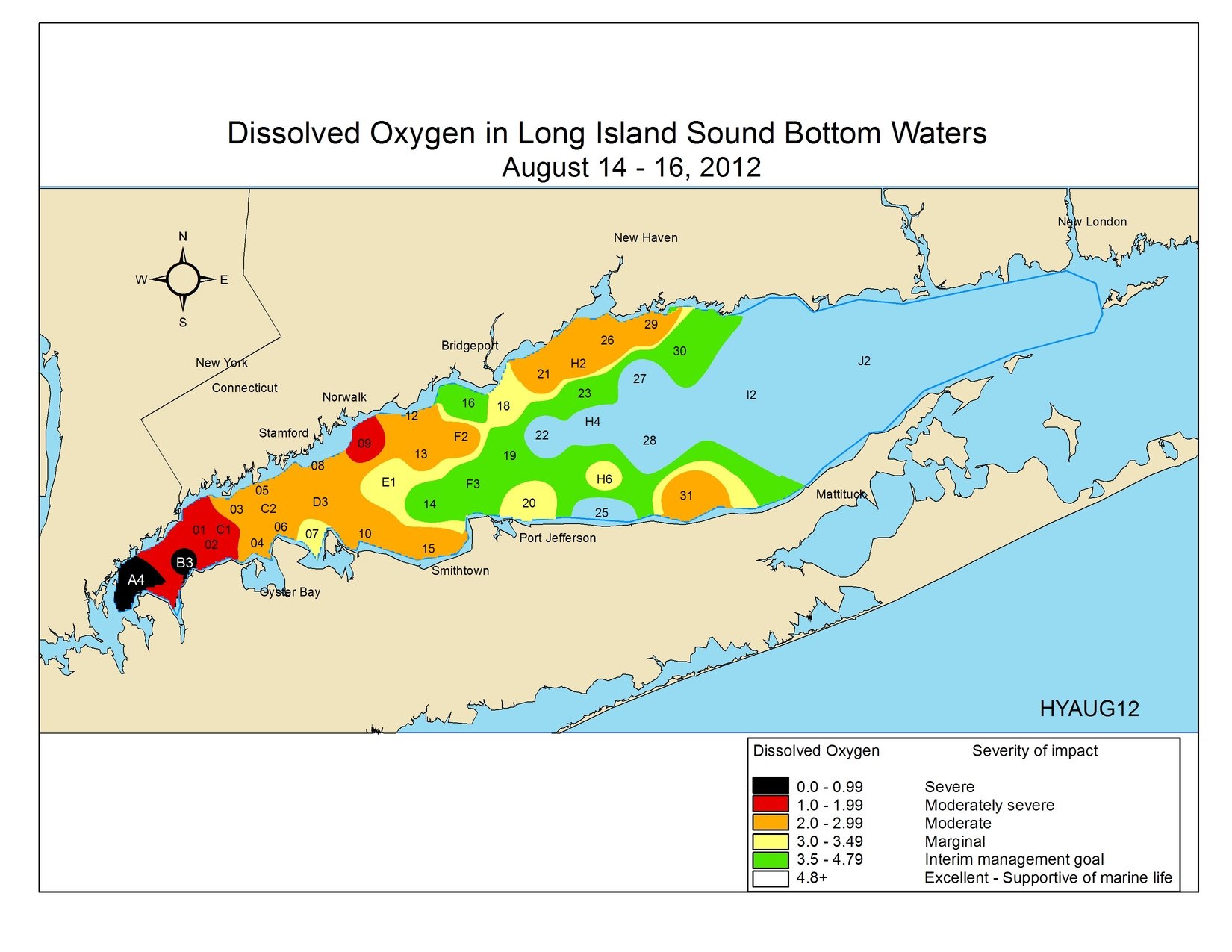

The Sound suffered from a spell of severe hypoxia, particularly in August. Hypoxia – low levels of dissolved oxygen, which makes parts of the Sound uninhabitable for marine life – is triggered by nitrogen in treated sewage. But thanks to a bi-state cleanup effort, the amount of nitrogen being dumped into the Sound is less than it has been in decades.

In other words, there is less of the pollution that triggers hypoxia. So why was hypoxia more severe than in recent years? We asked Mark Tedesco, director of EPA’s Long Island Sound Study program, and Matthew Lyman, an environmental analyst with the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection. Both have been analyzing Long Island Sound data for years.

In an email, Mark wrote, “Our favorite question is what causes the variability year-to-year. The simple answer is the weather. But that’s just short-hand for saying we don’t know.”

Hypoxia is clearly affected the weather, specifically by wind and temperature, which affect currents and water temperature; the difference in temperature between water near the surface and water near the bottom is also crucial.

As part of its year-round monitoring work, the DEEP records water temperature throughout the Sound roughly twice a month. For the 10 months from January through October 2012, they took measurements on 16 occasions.

The researchers keep track of the highest and lowest temperatures recorded each month, and the average.

They’ve been doing this since 1991. As a result, they were able to compare temperatures from each research trip in 2012 (through October) with temperatures from the corresponding trips in the previous 21 years.

On nine of the 16 research trips in 2012, the maximum recorded temperature was the highest in 21 years; those highest temperatures include January, February and March, when the Sound is typically coldest. The minimum recorded temperature was the highest in 21 years on 15 occasions, including January, February, March and April. The average temperature on those 16 research trips in 2012 was the highest in 21 years on 11 occasions.

In other words, Long Island Sound was unusually warm in 2012 and it did not cool off as much as it typically has in the past.

Warmer water naturally holds less dissolved oxygen than cooler water. Warmer water also is more conducive to the growth of algae, which feed on nitrogen and remove oxygen from the water when they die and decompose.

Lyman wrote to us, “One peculiar observation that we made that may have had an impact on the hypoxic event this year was a persistent Sound-wide algal bloom. We first noted the abundant bloom in April and it was observed Sound wide during each survey since, even our December survey conducted this week.”

Typically, the big, damaging blooms of algae don’t appear until summer, and they disappear in fall, when weather patterns change.

Autumn weather is also important because it breaks down the stratification of the Sound that is another key to hypoxia. In summer, water near the surface is warmer than water near the bottom, causing the Sound to divide or stratify into two layers. Those layers don’t mix. So as dissolved oxygen concentrations fall in the deeper waters, they can’t be replenished with oxygen from near the surface. In 2012, the difference in the temperature between top and bottom was bigger than usual, and stratification was stronger than usual.

Tedesco, in his email, discussed the importance of weather patterns: “This is probably the area where the greatest enhancement in the science of LIS has been made over the past decade. We understand better the mix of mechanisms at play, with the main players being temperature, stratification, and wind direction and force….

“The difference between the surface and bottom waters is the key factor. Wind speed and direction are important as well. Winds from the west, southwest (the predominate summer wind pattern) strengthen stratification by moving more East River surface water to the east. Winds from the east-northeast, weaken stratification by pushing against that western surface water. Bottom and surface waters mix, aerating waters.

“So, the general explanation would be that warmer temperatures and a lack of mixing events maintained stratification and allowed bottom water respiration to deplete DO over a larger area for a longer time than recent years.”

Posted by Tom Andersen, NY program and communications coordinator for Save the Sound. Tom is also the author of This Fine Piece of Water: An Environmental History of Long Island Sound.

You should not point the finger solely at STPs; their N is under control via BNR upgrades the states spent millions on over the years. Nonpoint sources, e.g., people fertilizing their lawns, driving their cars, runoff from rain and plain dry atmospheric N deposition are also responsible and will be much more difficult to control.