Like many fishermen, I’ve used menhaden, or “bunker,” as bait. It’s hard to believe, but when you’re holding one of these small, oily fish, you’re holding a big piece of history. Menhaden have had a major impact on the economy and ecology of our Atlantic coast for centuries, supporting a multimillion-dollar fishery and feeding marine wildlife from striped bass to humpback whales.

Now this historic fish faces its own pivotal moment. Menhaden populations have plunged 90 percent over the past 25 years and the regulators responsible for their management will soon make a critical decision. On December 14, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) could finally help the depleted population recover by setting a coast-wide catch limit.

This moment is eerily similar to an episode from history.

By the late 1800s, menhaden were already important to farmers as fertilizer and controversial among fishermen. This industrialized fishery angered other fishermen who said their catches were being depleted. The U.S. Fish Commission convened in 1895 to sort out the menhaden mess and the century-old commission report reads as if it were written today:

“The fishery has encountered great opposition on account of its supposed injurious influence on the abundance of other fishes…The menhaden fishermen contend that there is no proof.”

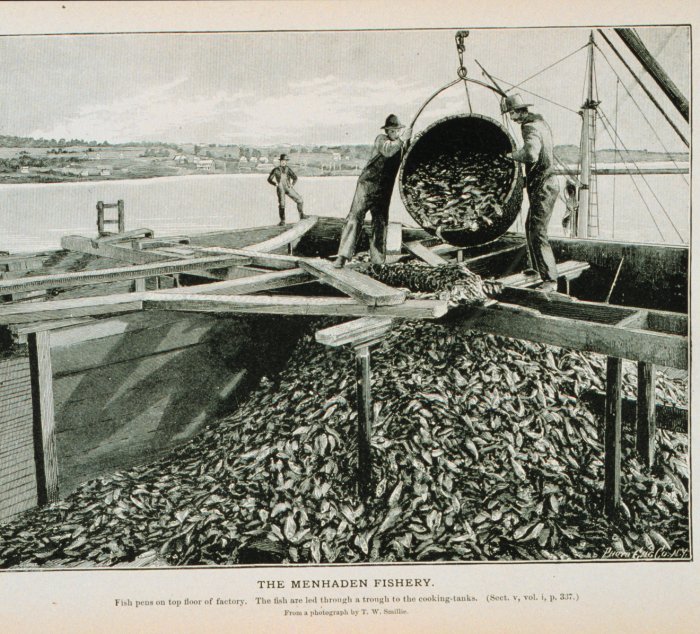

Photo: NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service

Faced with contradicting claims, the commissioners did what commissioners have long done. They called for further study, explaining:

“It appears probable that the menhaden fishery will for some years at least be the object of…controversy.”

They sure got that part right. The controversy persists 117 years later.

Today, menhaden still make up the largest fishery on the East Coast by weight. Boats supplying one factory take about 80 percent of the Atlantic menhaden catch, which is ground into feed for pets, livestock, and fish farms. But the menhaden’s ability to feed other marine creatures is at risk.

Whales, ospreys, bluefish, and tuna—all depend on these filter feeders to consume plankton and convert the energy into fat and protein. Yet this crucial component of the ecosystem is still not managed with modern best practices.

That could change come December, when the ASMFC commissioners can write a hopeful new chapter for this historic little fish.

Today’s post is written by Lee Crockett, Director, Federal Fisheries Policy for the Pew Environment Group. This post originally appeared in a longer form in his series, The Bottom Line.